Research: Correlates of tuberculosis risk: Predictive biomarkers for progression to active tuberculosis

SATVI authors, Mark Hatherill and Tom Scriba have co-authored "Correlates of tuberculosis risk: Predictive biomarkers for progression to active tuberculosis" appearing in the European Respiratory Journal.

New approaches to control the spread of tuberculosis (TB) are needed, including tools to predict development of active TB from latent TB infection (LTBI).

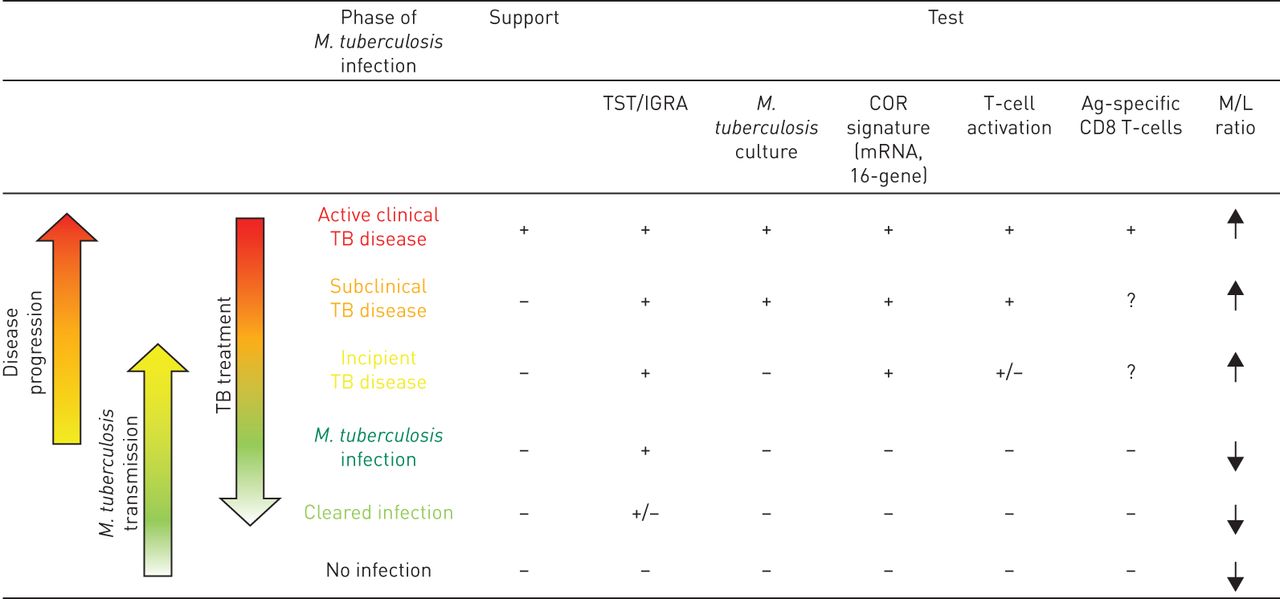

Outcome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis transmission and establishment of infection or disease based on the correlates of disease and correlates of risk. The outcome of a primary or secondary M. tuberculosis infection is not a simple two-state distribution represented by either active tuberculosis (TB) or latent TB infection, but rather represents a continuous spectrum of states that differ by the degree of the pathogen replication, host resistance and inflammatory markers. The identification of M. tuberculosis infection is complex, due to the absence of clinical signs, correlates of disease (COD), lung lesions detected by chest radiography or M. tuberculosis in the sputum culture. The latency state is characterised by an immunological equilibrium and by presumed control of the bacterial replication. As the infection advances, this balance is lost, resulting in increased bacterial burden and/or increased pathology. This state can be identified as subclinical or incipient TB disease, in which CODs may still be poorly informative. In contrast, correlates of risk (COR) may potentially allow the identification of those at risk, for preventive treatment. Indeed, upregulation of interleukin (IL)-13 and type I and II interferon (IFN)-related gene expression, elevated activation markers on T-cells (e.g. expression of D-related human leukocyte antigen and loss of CD27 expression), as well as an elevated monocyte/lymphocyte (M/L) ratio, have been shown to be predictive of TB disease development. The progression of subclinical TB to clinical TB is likely to be associated with a further increase in bacterial burden and/or pathology. Therefore, active TB diagnosis is based on CODs, including chest radiography findings such as lung lesions indicative of disease, detection of M. tuberculosis in sputum and positive COR tests. Transmission of M. tuberculosis from active TB patients may lead to a primary or secondary M. tuberculosis infection. Primary M. tuberculosis infection is defined by IFN-γ release assay (IGRA)/tuberculin skin test (TST) conversion and absence of radiological lung lesions and sputum negative for M. tuberculosis. ↓: downregulation; ↑: upregulation; +: presence of a modulation based on current knowledge; −: absence of a modulation based on current knowledge.

These efforts have included unbiased approaches employing “omics” technologies, as well as more directed, hypothesis-driven approaches assessing a small set or even individual selected markers as candidate correlates of TB risk. Unbiased high-throughput screening of blood RNAseq profiles identified signatures of active TB risk in individuals with LTBI, ⩾1 year before diagnosis.

A recent infant vaccination study identified enhanced expression of T-cell activation markers as a correlate of risk prior to developing TB; conversely, high levels of Ag85A antibodies and high frequencies of interferon (IFN)-γ specific T-cells were associated with reduced risk of disease. Others have described CD27−IFN-γ+ CD4+ T-cells as possibly predictive markers of TB disease. T-cell responses to TB latency antigens, including heparin-binding haemagglutinin and DosR-regulon-encoded antigens have also been correlated with protection.

Candidates of TB risk

| Biomarker | Neonates, children, adolescent or adult population | Location | [Ref.] | |

| Validated correlates of TB risk | ||||

| Commercial or traditional tests for LTBI diagnosis | RD1-specific immune response in IGRA, immune sensitisation to PPD in TST | Children and adults | Global | [22, 44, 45] |

| Molecular tests | mRNA expression signature of 16 IFN response genes | Adolescents | Africa | [52] |

| Cell activation markers | Increased HLA-DR-expressing CD4+ T-cells | Infants | Africa | [63] |

| Blood cell counts | Elevated monocyte/lymphocyte ratio | Adults | Africa | [111, 114] |

| Unvalidated correlates of TB risk | ||||

| Molecular tests | IL-13 and AIRE mRNA expression signature | Adults | Europe | [58–60] |

| Elevated expression signatures of IFN response and T-cell genes | Infants with strong response to BCG vaccination | Africa | [115] | |

| Elevated expression signatures of inflammation, myeloid and glucose metabolism genes | Infants with weak response to BCG vaccination | Africa | [115] | |

| Antigen-specific T-cells | Increased IFN-γ-expressing Ag85A-specific T-cells | Infants | Africa | [63] |

| Increased Th1-cytokine-expressing BCG-specific CD4+ T-cells | Infants with strong response to BCG vaccination | Africa | [115] | |

| Cell differentiation markers | Downmodulation of CD27 in CD4+ T-cells | Adults | Africa | [76] |

| Serum/plasma cytokine tests | Increased levels of IP-10 | Adults | Africa | [86, 87] |

| Antigen-specific antibodies | Elevated levels of anti-Ag85A-binding IgG | Infants | Africa | [63] |

| Responses to latency antigens | IFN-γ response to in vitro stimulation of PBMCs using HBHA | Adults | Europe | [95] |

| IFN-γ response to in vitro stimulation of whole blood using Rv2628 | Adults | Europe | [103] | |

| CD8+ T-cell response | IFN-γ response to in vitro RD1 stimulation of PBMCs | Children and adults | Africa Europe | [37] |

Acronyms: LTBI: latent TB infection; RD: region of difference; IGRA: interferon (IFN)-γ release assays; PPD: purified protein derivative; TST: tuberculin skin test; HLA-DR: D-related human leukocyte antigen; IL: interleukin; AIRE: autoimmune regulator; BCG: bacille Calmette–Guérin; Ag: antigen; Th: T-helper cell; IP: IFN-γ-inducible protein; Ig: immunoglobulin; PBMCs: peripheral blood mononuclear cells; HBHA: heparin-binding haemagglutinin.