How COVID-19 May Change Mask-wearing Practices in Clinics and Public Places in South Africa

Idriss Kallon (Researcher, UCT)

Editorial Note: Idriss Kallon is a postdoctoral researcher in the Division of Social and Behavioural Sciences working on an interdisciplinary research project about tuberculosis infection prevention and control in primary health care settings in the Western Cape and KwaZulu-Natal provinces in South Africa. The project is a collaboration between the Division of Social and Behavioural Sciences at UCT, the University of KwaZulu-Natal, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (UK), and Queen Margaret University (UK).In this piece, Idriss shares how COVID-19 may change mask-wearing practices in clinics and public places in South Africa. The piece also reflects on how consistent political messaging on mask-wearing may enhance proper mask-wearing in clinics and other public places in South Africa.

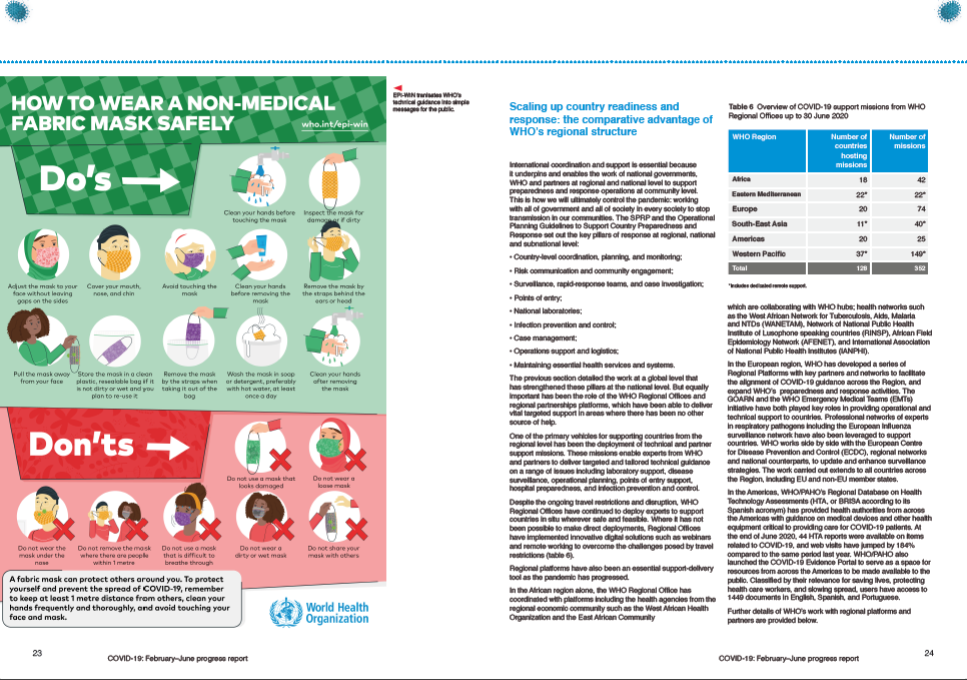

Mask-wearing was an important part of the infection prevention and control (IPC) practices to combat the influenza epidemic of 1918, and it has the same importance to combat the novel corona virus (or SARs-COVID2), commonly known as COVID-19, a virus discovered in Wuhan China in December 2019.1 Face masks can protect someone from contracting COVID-19 when you come in contact with an infected person as well as preventing onward transmission.2 Before the COVID-19 pandemic, balancing the essence of mask-wearing and avoiding stigma in the context of tuberculosis (TB)-IPC, for example, has been a problem in some clinics in South Africa. This is because sometimes when a patient was asked to wear a mask, especially the N95 respiratory mask, with its unique shape, other patients thought you had an infectious disease such as tuberculosis (TB).3,4 Drawing on examples from a TB project entitled Umoya Omuhle: policy, systems, and organisation of care for TB-IPC in KwaZulu-Natal and Western Cape, South Africa4,5, this piece presents some reflections on how COVID-19 may change mask-wearing practices in South Africa and erode or minimise the stigma that patients feel when asked to wear a mask. This study is an interdisciplinary whole-systems research in 12 primary health care clinics in the Western Cape and KwaZulu-Natal. This piece draws on initial findings from the daily practices of health workers and the organisation of care of six Western Cape primary health care facilities. Furthermore, it discusses how consistent political messaging on proper mask-wearing could complement the changing discourse on mask-wearing in clinics and other public places in South Africa. Government websites and presidential addresses on National television are some of the key media platforms that inform the public about the progress of the COVID-19 pandemic and can positively impact behaviour on appropriate mask-wearing.

WHO Guidlines on Mask-wearing

Mask Wearing Context in South Africa Before Covid-19

Challenges of wearing masks in clinics

Based on responses from staff and patients and personal observations in six primary healthcare clinics in the Western Cape, from the Umoya Omuhle TB project described above, mask-wearing has not been consistent. This includes the wearing of all types of masks - N95 respirators, mostly worn by staff, and surgical or paper masks that are worn by patients. There are several reasons provided for this inconsistent wearing of masks in clinics, which include avoiding or preventing stigma.

Discomfort of Wearing Masks

Many staff complained that the masks, especially the N95 respirator masks that they normally wore, were uncomfortable. It is even worse if someone had flu and needed to wear a respirator mask. They complained it was also stuffy, smelled awful and it felt they could not breathe properly when they wore the N95 mask. Some patients who either did not wear their surgical mask (in some cases, N95 respiratory mask), or did not wear them properly, also complained about the discomfort of wearing masks. As a result of this, many patients wore masks not covering their nose or the mask would be hung around their neck when sitting in the waiting areas in the clinic. Masks were mostly worn properly when patients were in the consulting rooms being treated by healthcare staff.

Avoiding or Preventing Stigma

Some staff did not wear a mask when seeing patients in order to prevent patients feeling stigmatised. Some of the healthcare staff mentioned that patients took offence when they (the healthcare staff), wore their mask when treating them because not all of them had an infectious disease. The patients also grumbled that whenever they wore masks, some people thought they had TB.

Unavailability of Masks or Not Displayed Upon Entrance into the Clinic

In some of the clinics, staff members highlighted using one N95 mask for the whole week, instead of using one mask for 8 hours per day, which they indicated was the recommended time to use the N95 respiratory mask. Some clinics we visited did not display surgical masks or paper masks for patients to use at the entrance. This did not always mean that there were no surgical or paper masks available, rather they were not displayed for patients to use before entering the clinic because of lack of proper infection control management. In some cases, large community health centres that saw about 3000-4000 patients per month could not afford to give every patient a mask.

Although patients going to certain areas in the clinic showed that they were accessing treatment for an infectious disease, like TB or drug-resistant TB for example, the fact that everyone must wear a mask to prevent COVID-19, may have potentially eroded the feelings of stigma. Furthermore, there have been changes in poster information in the clinics that intensified the essence of mask-wearing. The new information posters are also posted in many government buildings, schools, universities and other public places in South Africa.

South African Government Online Messaging on Mask-wearing and During National Addresses

On the COVID-19 South African Resource Portal (online resources and news platform), the preventative measures stipulated including proper hand washing, avoid touching one’s face with unwashed hands and avoiding close contact with people. The use of mask-wearing or the proper use of mask-wearing is not stipulated on the first page, which may capture people’s attention immediately.7 It is only when you navigate further are you able to see several videos that explain the essence of wearing a face mask and how they should be worn.7 It is unlikely many people would go through that navigation process for more information.

In addition, there are several addresses from the South African President, Cyril Ramaphosa, and other members of government that highlighted the use of masks. This included a demonstration by President Ramaphosa who struggled to put on a face mask.8 The president later declared jokingly that he would start a TV channel to show the public how to wear mask properly. If that were actually carried out, that could possibly have been a great help to the public. Alternatively, a follow-up from the Department of Health could have captured public interest on how to properly wear a face mask. However, in most cases, the emphasis is on covering your mouth and nose when sneezing or simply wearing a mask rather than wearing it properly. There are other messages that have been communicated to the public through speeches by the President regarding preventative measures against COVID-19.9 These include the president’s address to the nation on 24 March 2020, a few days after declaring South Africa a “state of disaster” and on 23 April 2020.

“We reiterate that the most effective way to prevent infection is through basic changes in individual behaviour and hygiene. We are therefore once more calling on everyone to: - wash hands frequently with hand sanitizers or soap and water for at least 20 seconds; - cover our nose and mouth when coughing and sneezing with tissue or flexed elbow; - avoid close contact with anyone with cold or flu-like symptoms. Everyone must do everything within their means to avoid contact with other people. Staying at home, avoiding public places and cancelling all social activities is the preferred best defence against the virus.”

“If we all adhere to instructions and follow public health guidelines, we will keep the virus under control and will not need to reinstate the most drastic restrictions. We can prevent the spread of coronavirus by doing a few simple things. Wash your hands frequently with soap and water or use an alcohol based sanitiser. Keep a distance of more than one metre between yourself and the next person, especially those who are coughing and sneezing. Try not to touch your mouth, nose and eyes because your hands may have touched the coronavirus on surfaces. When you cough or sneeze cover your mouth and nose with your bent elbow or a tissue, and dispose of the tissue right away.”

From the above messages regarding the most important preventative tips to the public, there is no emphasis on wearing of masks neither to wear them properly. In other addresses to the nation, for example, incorporating the proper use of mask-wearing was included [7]. On 12 July and on 1 August 2020, statements by President Ramaphosa on progress in the national coronavirus response, he said:

"We are by now all familiar with what we need to do to protect ourselves and others from infection. We need to wear a cloth mask that covers our nose and mouth whenever we leave home. We must continue to regularly wash our hands with soap and water or sanitiser.

Above all, we need to continue to follow prevention measures to reduce the rate of infection and flatten the curve. By wearing a mask correctly, keeping a distance of two metres from other people, and washing our hands regularly, we can protect ourselves, our families, friends, co-workers, fellow commuters and neighbours.

Concluding Thoughts

COVID-19 may have changed some of the practices regarding mask-wearing in clinics and public places in South Africa. For example, poster information displaying the consistent use of masks and how they should be worn help intensify the need to wear mask in clinics and public places. It may have helped in eroding or minimising those who feel stigmatised when they are asked to wear masks. However, the messaging around wearing masks has not been consistent from the South African government. There have been improvements in combating the COVID-19 pandemic in the last month in South Africa, where daily incidence has dropped from 13285 on 18 June 2020 to 2541 on 17 August 2020. This means the South African government and other stakeholders have done well in many aspects to control and manage the COVID-19 pandemic in the country. Since mask-wearing has been proven to be instrumental in combating infectious diseases in the world, its use in the clinics must be normalised even after COVID-19 and potentially destigmatise mask-wearing for patients and staff at the clinics. In addition, the messaging around mask-wearing from high-profiled individuals must be very consistent to complement the other measures to combat the COVID-19 pandemic. The president’s address to the nation must always include the proper use of masks alongside other important COVID-19 measures. The governmental online resource platform as well, should be modified to include proper mask-wearing as part of the preventative tips that can be immediately seen by viewers.

References

1. Leung, C.C., Cheg, K.K., Lam, T.H & Migliori, G.B. 2020. Mask wearing to complement social distancing and save lives during COVID-19. Editorial. Available from:

https://www.theunion.org/news-centre/news/body/IJTLD-June-0244-Leung-FINAL.pdf

2. World Health Organisation. 2020. Advice on the use of masks in the context of COVID-19. Interim Guidance. 5 June 2020. WHO: Geneva. Available from:

https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331693

3. Abney, K. 2018. “Containing” tuberculosis, perpetuating stigma: the materiality of N95 respirator masks. Anthropology Southern Africa. 41(4):270-283. Available from:

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/23323256.2018.1507675

4. Kallon, I.I. 2019. Personal Protective Equipment for Tuberculosis Infection Prevention and Control in the Western Cape: Disjunctures Between Policy and Practice. Fieldnotes. Division of Social and Behavioural Sciences. University of Cape Town. Available from:

http://www.dsbsfieldnotes.uct.ac.za/news/personal-protective-equipment-tuberculosis-infection-prevention-and-control-western-cape

5. Umoya Omuhle: Policy, Systems, and Organisation of Care for TB Infection Prevention and Control in KwaZulu-Natal and Western Cape, South Africa. 2017. Project Research Proposal. Available from: https://www.lshtm.ac.uk/research/centres-projects-groups/uo

6. World Health Organisation. 2020. WHO COVID-19 preparedness and response progress report. 1 February to 30 June 2020. WHO: Geneva. Available from:

https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/who-covid-19-preparedness-and-response-progress-report---1-february-to-30-june-2020

7. COVID-19 South African Resource Portal. Online Resources & News Portal. SAcoronavirus.co.za. Available from: https://sacoronavirus.co.za/

8. South African President Cyril Ramaphosa mocked over face mask struggles. BBC News Africa. 24 April 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-africa-52414885

9. The Presidency. Republic of South Africa. Available from:

http://www.thepresidency.gov.za/speeches/statement-president-cyril-ramaphosa-escalation-measures-combat-covid-19-epidemic%2C-union

Author Biography

Email: iikallon@gmail.com