Research With Adolescent Boys and Young Men Living With HIV – Reflections on Ethical Challenges During Fieldwork in the Eastern Cape

Lesley Gittings (Researcher, UCT)

Editorial Note: Dr Lesley Gittings is a postdoctoral researcher with the Accelerate Hub, based at the University of Cape Town. Her work focuses on participatory methodologies with adolescents and young people. Her research interests include HIV, masculinities, adolescence and traditional and biomedical approaches to health and wellness. In this blog post, Lesley reflects on the ethical challenges during her PhD research with adolescent boys and young men living with HIV in the Eastern Cape in 2017 and 2018. Her research was conducted with the Mzantsi Wakho study. For more information on Mzansti Wakho, including main research partners and funders, please visit: http://www.youngcarers.org.za/youthpulse.

In February 2018, our research team went to request a follow-up interview with a young man. He was 23 years old and lived in a rural area outside of King William’s Town. In our initial interview the year before, he participated actively, seemed to enjoy the interview and consented to be contacted again for another one. When we tried to follow up with him telephonically to request a second interview, the phone numbers we had on file for him were no longer working. This was common with a group of highly mobile young people. We took the research vehicle, pictured below, and set out to the participant’s home.

There were a number of reasons for bringing this vehicle. Firstly, these steady bakkies (pick-up trucks) are capable of driving rural roads. The closed-back cabs are outfitted with benches and were sometimes used as an interview space when participants did not want to be interviewed at home or at another location. This bakkie (pictured above) is one of a number of similar looking Mahindra trucks, all of which had been brightly spray painted.

Upon arriving outside of the participant’s home, his neighbour started calling loudly for him. He did not emerge, and we decided to leave, not wanting to bring more attention to him. Our concern was that he was home but choosing not to come out of his house. ‘Stigma mitigation’ that is, taking measures to reduce the risk of stigmatising participations, was an important aspect of the study.1 It was a central concern because the research was conducted in environments of high surveillance, where people were observant of and interested in the presence of researchers, and because of the highly stigmatised nature of HIV. For these reasons, the fact that the study focused on HIV was not disclosed to participants. Within the broader study, and particularly within its qualitative component, many research questions were expansive and open-ended. The wider quantitative component of the study also included about 500 young people whose HIV-status was unknown. When it was introduced to participants by researchers, the study was broadly framed as being about young men and health. However, given that the research vehicles were highly visible, we wanted to ensure that they were not identified as related to an HIV research project; which might automatically disclose a participant as living with HIV.

A few days later, we used a different approach to visit the participant. A male driver and one of the qualitative researchers on this sub-study (and a co-author of this article), drove together to the participant’s home in a smaller and more ordinary looking car. When they arrived, the participant answered the door and agreed to be interviewed. He was dressed stylishly in a crisp white t-shirt, jeans and wore a large wooden cross around his neck. He had a severe-looking rash over his face and visible parts of his body. He said he was available for an interview, and asked that the interview take place at KFC in King William’s Town.

In the car on the way to the interview, the participant, unprompted, opened up to the researcher and driver. He told them that he had stopped his HIV medicines since coming back from initiation in 2012, six years prior. This finding, that young men defaulted from their medicines after return from initiation, emerged among a number of participants. The participant, Ta Saider (a pseudonym selected by the participant) also spoke about how, prior to initiation, he had ‘part-timed’ (that is, took his pills sometimes, but not always) on his medicines and disclosed that he did not want to go back to the health facility because the sister-in-charge used to shout at him. Feeling ‘exposed’ in the clinic and unfriendly staff were common barriers for young people not to visit the clinic or discontinue medication. Ta Saider expressed his concern that he might get sick because he hadn’t taken HIV medicines for a long time. He also requested support from the researchers on a matter that he had not spoken to anyone about. He said that his foreskin was not completely removed during traditional circumcision and asked for information about how to get medically circumcised. He raised his concerns about his medicines-taking and foreskin again during the interview when he was asked about which areas of his life that he wanted to improve. Here he speaks about the term ‘cutting’ in relation to both his remaining foreskin and his perceptions of associated health risks:

Ta Saider: Like to what we have talked about, circumcision and health… I want to go back to my treatment, as I was defaulting on treatment. I want to be circumcised. I have already done that, but I want to cut that 30% and also take my treatment.

Interviewer: When you talk about 30% what do you mean?

Ta Saider: The 30% - you are cutting the high risk of HIV.

Interviewer: So you want to go back and cut?

Ta Saider: I want to go and cut again because in initiation they did not do the proper

cutting. They said I’ve got a thick foreskin. So if I could cut again my health will be

good, and I can go back to treatment.

Interviewer: Did you go and try and ask at a clinic or hospital?

Ta Saider: No I have not done that yet.

Interviewer: You said before that you want me to ask for you where you can get help?

(referring to car ride to interview)

Ta Saider: Yes I want that.

(Ta Saider, 21)

This interview revealed several ethical issues which are complex and difficult to navigate. The participant disclosed that he was not taking essential medicines, and it is possible that his rash was a symptom of an opportunistic infection due to his weakened immune system. He requested support in re-engaging with biomedical health services, but did not want to present at the same health facility in his area. He also asked for help to access another biomedical intervention: medical male circumcision. But his rationale for wanting to get medically circumcised demonstrated that he had incorrect information about the benefits of medical male circumcision. As he was already HIV-positive, ‘cutting the high risk of HIV’ did not apply to him, showing that he had received and internalised circumcision-related messaging but did not have a proper understanding that the protective benefits of HIV-risk reduction are for men who are not living with HIV.

Following this, we tried contacting the participant on the more recent phone numbers he had given us, but couldn’t reach him. The researchers went back to his house in the same discrete car but didn’t find him at home. Not wanting to stigmatise him, we did not follow up again. A few weeks later we went to review clinic files at the health facility that he used to attend. His file showed that he had presented recently at the facility for the first time in years.

This case study is described here to offer insight into some of the complex ethical challenges faced in the course of this study, which required a range of methodological solutions. Although a unique case, it highlighted broader common challenges in conducting HIV research with young people living with HIV in resource-limited and high surveillance settings. These challenges included: (1) participant disengagement from essential biomedical health services and medicines; (2) participants requesting referral support from the research project; (3) difficulties reaching research participants; and (4) stigma mitigation and visibility issues with research vehicles in high surveillance areas.

These are each discussed briefly below.

Firstly, the research protocols stated that in cases where participants disclosed non-adherence to essential medicines, that the interviewer would discuss the importance of adherence with the participant and also encourage them to consult a healthcare worker or adherence supporter. In this case, the participant spoke about his mistrust of his health worker and his reticence to return to his health facility with researchers. But researchers feared alienating the participant by encouraging or insisting that he go back to a health facility at which he felt uneasy, and did not want to scold him about not taking his medication.

Second, the referral protocols map out the process for referral cases. Some cases – such as sexual assault – required mandatory reporting, whereas others, such as food insecurity and substance abuse were more common. This sub-study received a significantly higher proportion of requests for support and referrals than the Mzantsi Wakho study, the large mixed methods study within which this research project was housed. That is, these requests posed both an ethical and methodological challenge. We wished to be supportive, but did not want to create alternative systems through which participants came to rely on the project and, foreseeably, would feel abandoned after its completion. We also did not want to skew study findings by intervening and had limited human and financial resources to provide support.

We managed this by streamlining the referral process into the broader Mzantsi Wakho referrals. We also tried to ensure that the referrals we conducted provided options for greater sustainability. For example, when delivering food parcels, we included seeds so that participants might grow their own food (if they desired to do so and resources such as land and water availability and arable soil pending), and we aimed to refer participants to accessible referral partners, such as counselling services. We also took notes about the referrals, and reviewed these when going back to participants. In the case of the participant above, despite not reaching him directly to provide a referral to a health facility, it is likely that our intervention resulted in him reengaging in HIV care.

Third, reaching research participants was often challenging with changing phone numbers and homes. We also wanted to balance our understanding of their informed consent. That is, we wanted to balance their requests for support with their privacy and the possibility that they did not want to be contacted again. In some cases, like the one above, this was unclear. He actively chose to participate in an interview and repeatedly requested support. Whether he was intentionally unavailable when we tried to respond is difficult for us to know.

Last, during the study design phase and throughout the study, extensive efforts were taken to minimise risks of stigmatising participants. Some of these are described briefly above, and they are mapped out comprehensively in the research protocols. However, in the car on the way to the interview, the participant, Ta Saider, said explicitly that he did not want to be associated with a Mahindra (most of the project vehicles were the same highly-visible kind of car). He did not explicitly link this to his HIV status, but it is possible that he had made the connection:

Interviewer: So you were saying once the Mahindra stops in front of your house they

assume that there is something wrong?

Ta Saider: Yes. As I am a secretive person so I don’t want anyone to know my status.

Interviewer: So what have they suspected now?

Ta Saider: No there is nothing, but as I think that it can cause problems

Interviewer: So you don’t want to see the Mahindras?

Ta Saider: No.

(Ta Saider, 21)

That he did not want to be seen associated with a Mahindra on its own is an ethical concern. Despite the stigma mitigation measures described above, including interviewing family members and neighbours, after almost three rounds of interviews with most of the study’s approximately 1500 participants (over a 1000 of whom are HIV-positive), this interview suggests that some participants had linked our study to HIV. The participant did not want to be associated with that Mahindra, but also wanted to be interviewed.

Did we do the wrong thing by going back to his house in a different car? Were other community members aware that Mahindras were linked to an HIV study, or had the participant speculated that the study was HIV-related and was worried about being seen in the Mahindra? If it was the former, what might be the effects been of this inadvertent disclosure and stigmatisation on his, and other young people’s lives? Did we harm this participant through stigmatising him or causing him to worry about stigma?

At the same time, is it possible that he also benefited by taking part in the research by being provided the opportunity to speak openly with supportive adults outside of his regular day-to-day interactions, and being encouraged to re-engage in clinical care? Was there, like he and other participants sometimes suggested, therapeutic benefit to taking part in this research? And if so, was the benefit enough to outweigh potential harms and make it worthwhile for them to participate? In choosing this research encounter, how much agency did he have? And was taking his word at face value about his interest in participating affirming of his agency, or might we have missed something? And, will the findings of this research be able to shape further research, policy or intervention in a way that benefits a larger group of young people, who are facing the same challenges?

Although we aim not to harm participants, this case study is an example of how research is never neutral. It speaks to a multiplicity of ethical quandaries and related methodological challenges present in research with young people living with HIV in contexts of precarity and constraint. They are raised here as questions, with the acknowledgement that these are unanswerable in a simple way. These questions speak to some of the complexities of benefit and harm implicit in this research.

As researchers, a central part of our work is trying to answer questions so that we can create knowledge. However, we have also tried to resist the urge to definitively answer certain uncomfortable questions. Our hope is that we might learn from sitting with this discomfort and be accountable to the shortcomings of our methods. And, that in being more responsive to participants, that we might co-create meaningful knowledge with them.

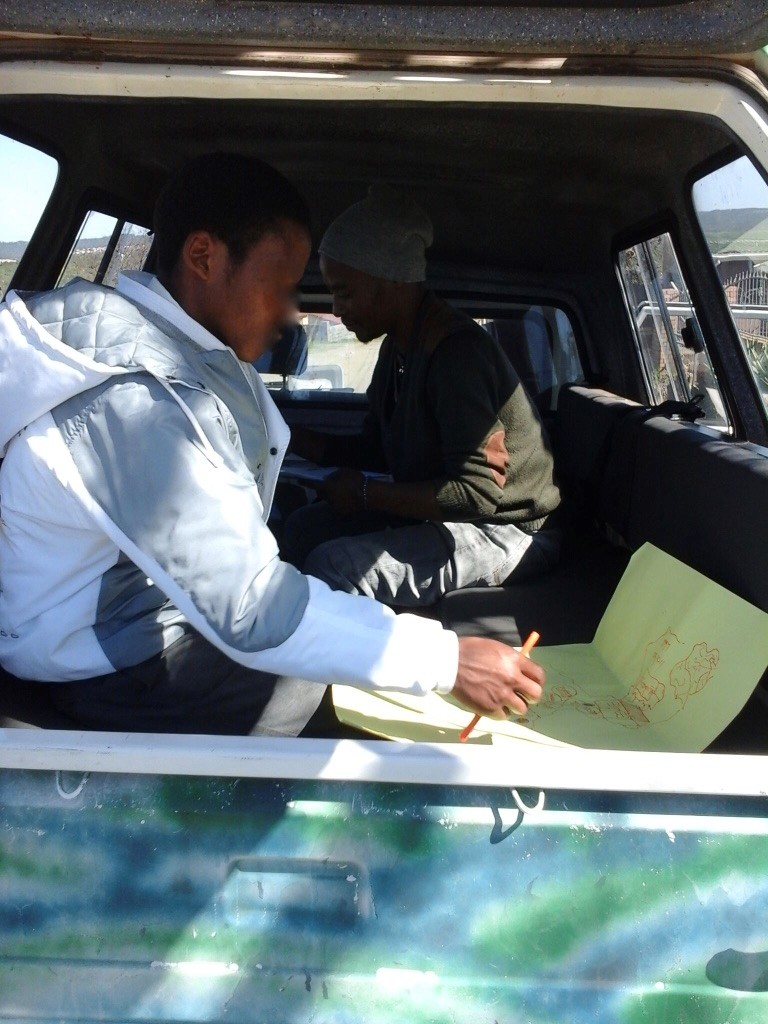

Image Captions:

Image 1: The beast of a research vehicle

Image 2: Researchers Sinebhongo Mbula and Phakamani Kom conducting a home visit of a participant, rural Amathole, Eastern Cape

Image 3: Participant conducting life history narrative interview

Reference

Toska E, Culver LD, Hodes R, Kidia KK. Sex and secrecy: How HIV-status disclosure affects safe sex among HIV-positive adolescents. AIDS Care. 2015;27(sup1):47-58.

Collaborators

Rebecca Hodes (Researcher, UCT); Christopher J Colvin (UCT, Researcher); Sinebhongo Mbula; Phakamani Kom

Author Biography

Email: Lesley.Gittings@gmail.com