Adventures, Archives, and AIDS Research

Carla Tsampiras (Senior Lecturer, UCT)

Editorial Note: Carla Tsampiras is a Senior Lecturer in UCT’s Primary Health Care Directorate. Her work is concerned with understanding how constructions of ‘race’, gender, sexuality, and class influence understandings of, and responses to, health concerns. In this piece she reflects on her experiences in sifting through archives and how archival information is important to help us understand and respond to AIDS and HIV.

Take a moment to think about the first time you heard about AIDS or HIV. What did you hear? Where did you hear it? When did you hear it, and how did it make you feel? I have been asking these questions in lectures and presentations for over a decade in numerous countries and contexts. There are always new answers and positive experiences shared alongside a number of die-hard myths and negative experiences. Almost 40 years into the HIV and AIDS epidemic it can sometimes be difficult to remember that epidemics and the people and places they affect, have a myriad histories. Some of the people who answer these questions remember the world before the epidemics and others have never lived in a world without HIV and AIDS.

With our life stories, our personal and professional interests, our HIV status, and our public and private engagements with the epidemics, we all hold personal archives related to HIV and AIDS. Health historians spend much of their time shifting through various types of archives to write histories about health and healing that show what occurred in the past and analyse how that continues to shape the present. Oral histories and testimonies remain an important source for health historians and others interested in AIDS research. Oral sources, however, are only one type of ‘archive’ available and finding other AIDS archives can often be an adventure for intrepid researchers.

My thesis, Politics, Polemics and Practice: A History of Narratives about, and Responses to, AIDS in South Africa, 1980 – 1995, completed in 2012, looked at the early years (1980-1995) of what was to become known as the AIDS and HIV epidemics in South Africa. I was particularly interested in how political and medico-scientific elites shaped the discourse about, and practical responses to the emerging epidemics. The course and form of my research was shaped by my curiosity, solving problems like how to search for information in libraries for the time when the epidemics were underway but the terms ‘AIDS’ and ‘HIV’ had not been settled on, and by what was available in archives.

For health historians working on histories of AIDS in South Africa this can certainly be the case as interviewees or heads of organisation not only share their stories but also drawers, filing cabinets, store rooms, libraries, or personal correspondence. Whether well organised or stuffed in a box, these ‘ad hoc archives’ are a particular treasure to historians. As with oral interviews, interviewees and ‘ad hoc archives’ are not equally available to all researchers, or to interested parties more broadly. Personality, privilege, persistence and any other number of factors that shape interpersonal relationships can determine what is shared or what is left unspoken or unseen. This is not unique to research into AIDS histories, and is one of the interesting components of any research involving personal interactions with others. When researchers share their work and the knowledge they have been able to access they contribute a tile to a mosaic that creates a more complex and nuanced picture of the topic under discussion.

For many activists and people involved in NGOs or CSOs, archiving may not be a high priority in the face of addressing the urgency of a specific crisis or campaign. This means that organisational knowledge and source documents that can be important to historians – like minutes or memoranda – can be difficult to obtain or track down. This situation is made more complicated by a lack of resources and support that far outweighs the necessity to secure archives of ‘ordinary’ people or organisations.

It is for this reason that archives housed in universities or research institutes can take on great significance as they may hold material on ‘ordinary’ and ‘extraordinary’ people and organisations. The University of Fort Hare library, for example, holds a number of liberation archives, including those of the ANC in exile. This written archive includes correspondence, memos and minutes of the ANC regional health teams, the ANC health secretariat (or health department) and the National Executive Committee; and conference and seminar reports and papers. Meanwhile, a seminal ANC AIDS information video was serendipitously tracked down in the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam after a five-year search. Organisational archives allow us to see how thinking in an organisation may have changed or been contested, or to work out what factors may have shaped the courses of action decided upon and who decided them.

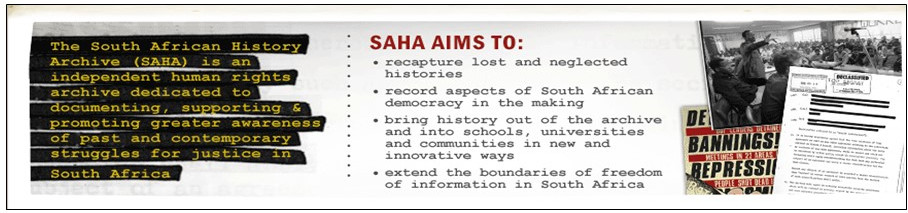

Various archives held at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits) provided the majority of the documents for the thesis. The remarkable ‘archive for justice’ the South African History Archive (SAHA) (then based at Wits) and important Historical Papers research archive had holdings on organisations that formed part of the progressive primary health care movement which shaped post-apartheid health policies and practices.

Of particular significance at Wits, is Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action (previously referred to as GALA - the Gay and Lesbian Archive) a phenomenal archive that holds collections relating to the personal lives or work of activists involved in anti-apartheid politics, sexuality politics, and AIDS activism. These personal archives as well as the archives of a number of sexuality organisations like the Gay Association of South Africa (GASA) and more overtly political groups like the Gay and Lesbian Organisation of the Witwatersrand (GLOW) and the Organisation of Lesbian and Gay Activists (OLGA) provided incredible insight into early strategies and struggles amongst sexuality activists.

The archives revealed the diversity and complexity of sexuality politics in South Africa and provided insights into some of the early responses to AIDS by sexuality organisations, from providing counselling, support and care, to organising lectures and distributing AIDS education information. It was also in this archive that correspondence from government officials (unobtainable elsewhere) was uncovered. Comprehensive histories of how various sexuality organisations responded to AIDS in South Africa still need to be written.

Responses of individuals and organisations to AIDS in the early days of the epidemic provide insights into important aspects of care, contestation and particular contexts in which responses are framed. Using archives and tracking responses to (and by) people and organisations can also reveal dominant ideologies that shape research into, and responses to health concerns. In the early years of the AIDS epidemic in South Africa, fear of ‘the other’, and inherent racism, sexism, and homophobia are abundantly evident. While this is not surprising, archives provide us with evidence that we can use to prove such analysis, track resistance to dominant ideologies, or see changes in ideologies over time.

Unlike NGOs, governments and government departments have a legal responsibility to ensure that official archives of public records are maintained at provincial and national level. The National Archives of South Africa Act 43 of 1996 framed how archives were to function in a post-transition South Africa. Sadly, despite the amazing work of activist archivists, the Archival Platform has shown that nationally and locally archives are in trouble. A project to update the main archival database - the National Automated Archival Information Retrieval System (NAAIRS) – started in 2011 and is still not complete. At the time of writing the entire database that links to all provincial archives is not available for searching.

When I did my research at the National Archive in Pretoria several years ago, finding conventional archival sources for writing a chapter on official government responses to AIDS was even more complicated than usual. In addition to the time restrictions applicable to official sources, and the purging of documents that has taken place by numerous South African governments, there is a substantial backlog in the cataloguing of available government documents due to a lack of resources, staff, and space. There are hundreds of metres of uncatalogued government records from the 1980s and 1990s.

Information on government responses had to be pieced together using a variety of alternative sources, such as the Hansard which records all debates in parliament and is still available in some libraries, the Annual Reports of the Department of Health which can be found in the National Library of South Africa in Cape Town, and complete collections of certain government publications held in university libraries. Histories can certainly be pieced together by numerous means, but when there is a responsibility to ensure public records are available to any interested member of the public, then they should not have to be.

The nature of archives are such that what is included in them, what is omitted, and what is made available to researchers are influenced by the politics of record keeping, and historians and other researchers have to work within that reality. Nonetheless, the constitution protects our rights to access information and that is a struggle that is being fought over current and past information. The state of the national archives, and what appears to be a failure to deposit current official documents, is going to have serious repercussions not only for historians, but also for members of civil society, and those interested in health and health care and in holding governments accountable. We all need to have adventures in the archives and all forms of archives that will help us understand and respond to AIDS and HIV are important and worth protecting, particularly, as Berridge notes because ‘[t]he political and ideological battles over the interpretation of the present are intense’. 1

Reference

1. Berridge, V., 'Researching Contemporary History: AIDS', History Workshop, 38, 1994, p. 228.

Author Biography

Carla obtained her Masters in African History from the School of Oriental and African Studies, UCL, UK and her PhD from Rhodes (sic) University, South Africa. She is currently a Senior Lecturer in Medical and Health Humanities in the Primary Health Care Directorate at the University of Cape Town.

Email: carla.tsampiras@uct.ac.za