Navigating Being a Mother and Low-Income Work in Urban and Rural KwaZulu-Natal

Nonzuzo Mbokazi (PhD Candidate, UCT)

Editorial Note: In this piece, PhD candidate and DSBS staff member Nonzuzo Mbokazi shares reflections on the findings from her PhD thesis titled, “Understanding low-income working mothers and childcare state policy in urban and rural KwaZulu-Natal”. This piece is dedicated to low-income mothers and their resilience in creatively managing the pressures of caring while living in severely financially constrained circumstances. All the participant names in this piece are pseudonyms. They are used to protect identities and maintain confidentiality.

Dominant discourses around motherhood have emerged from “Western” history and ideas and are also deeply patriarchal. In a society which upholds a certain restrictive version of “ideal motherhood” but is plagued by high unemployment, unequal gender relations, and absent paternal figures, these women must continually battle the considerable tension between their role as mothers and their roles as labour force participants. In this article, I briefly describe these discourses in more detail, and then consider the effect of these discourses on low-income South African women and their conceptions of mothering. I also explore the dual burden of paid labour and unpaid care work for low-income employed mothers in South Africa.

The underlying concepts informing notions of “ideal motherhood” in a Euro-centric discourse have generally been that a mother should be all-giving and self-sacrificing (1,2,3). Mothers are expected to find ultimate fulfilment in this role (3,4,5). This discourse has also resulted in a continuously reproduced ideal: that women should be “natural mothers” (i.e. instinctively able to care for and love their children) and that being a mother should be effortless (1,2,6). These ideals do not incorporate consideration of the extensive struggles often faced by mothers who do not have the luxury of being the kinds of mothers they personally and ideally would like to be, but must instead navigate and balance their competing roles as labour force participants and mothers.

The most prominent critique of the discourse of motherhood is that dominant theories and concepts about motherhood have been focused on the experience of white, middle-class, and heterosexual mothers (7,8,9). The traditional discourse on motherhood has been silent about the elements of structural, ideational and experiential oppression existing in some contexts, especially low-income contexts. This lack of awareness of the influence of these forms of oppression on low-income women’s experiences and configurations of motherhood were the impetus for this research.

The ongoing weight of this ‘second shift’ is particularly heavy for black women in the South African context, who historically have been disadvantaged on the grounds of race, gender and class. The advent of democracy in South Africa has allowed black women new opportunities (such as the ability to enter the labour force) but it has also imposed upon them new burdens: having to balance their public roles as labour force participants and their private roles as mothers. Although black women are entering the labour force in increasing numbers, the type of employment most available to these women is low-income employment, which is partly because black women were intentionally under-educated by the previous Nationalist government. Fathers are often absent due to choosing or being forced into the migrant labour system or for other reasons, and many are unable or unwilling to provide financial or emotional support. Rural women are also increasingly migrating to urban areas for work, often taking their children with them. Ironically, much of the paid labour that takes place among this group is caring for other (wealthier, usually white) women’s children, which has negative implications for how much time black women have available for caring for their own families. As a result of these various forces, most of the burden of childcare and breadwinning rests on the shoulders of low-income women.

In conducting this research and attempting to understand the lived experiences of low-income mothers, it was clear that the bulk (if not all) of the responsibility and duty to care fell on women alone. A pattern that ran across the 40 interviews I conducted was how low-income earning mothers are disadvantaged, both economically and socially. The low-income contexts in which my participants lived are considered “disadvantaged areas” and were all situated in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. In the urban context, this included townships and informal settlements (Umlazi and Sundumbili). In the rural context, this included rural settlements under a tribal authority (Macambini and KwaNdaya). For the purposes of this research, the categorisation of “low-income and working” included women with an income which is considered a low wage. Most were also beneficiaries of the government Child Support Grant (CSG) but overall, single mothers in my sample group did not earn more than R36 000 per year (R3 000 per month). If they were married, the combined earnings with their partner was not more than R72 000 per year (R6 000 per month) as per the CSG criteria in 2016, the year this research commenced.

In understanding the lived experiences of motherhood for low-income working mothers in urban and rural KwaZulu-Natal, a thread which ran through the interviews was how mothers considered motherhood to be both a gift and service. They felt that it was to be embraced and executed to the best of their ability. However, the ability to meet these standards was severely strained by enormous emotional, financial and sometimes physical struggles they faced. Women felt the weight and responsibility of their task heavily and talked about having to give a lot of themselves to ensure that they upheld the ideal of what it means to be a good mother. Sometimes this was experienced as being an exchange. While onerous, women also found it personally satisfying. Busi said:

“Being a mother makes you a creator, you have a responsibility to that creation. Your life changes completely because there is someone who needs you and who you need too. It means a lot to me because my child means everything to me, I love her with my all” Busi (Cleaner, 38 years old, 4 children)

Echoing Busi, Kholiwe (Factory Worker, 44 years old, 2 children) said:

“Motherhood is just about sacrifice, the moment you become a mother, your life is not yours anymore it’s theirs. You worry, you plan, it’s all for them. You need to be in touch with yourself spiritually, you need to realise that you have been given the duty of being a mother for a specific amount of time, once that child is 18, he is out of your hands so do your best when the child is still in your care and you have the ability to mould and shape them to becoming good and contributing members of society”.

Through these quotes it is possible to identify conceptions of motherhood which propagate the notion that once you are a mother, focusing on oneself is considered selfish or self-centred. A mother can no longer place herself at the centre of her life – her child/children must take centre stage. This is accompanied by the idea that motherhood and mothering entails being able to withstand the trials and tribulations which come with this role. A “good mother” must ensure a stable environment for her child(ren), a task that is always difficult but is especially hard within impoverished contexts. Women from poor backgrounds felt that they needed huge reserves of strength and resilience to accomplish their mothering roles. For Gabisile, this strength was exemplified by some women’s ability to put their children and role as a mother first, enjoying their care work, and being grateful for being given the opportunity to be a mother regardless of their circumstances. She explained further:

“It is incredible. I love being a mother, it so rewarding to know that when you get back from work there is someone who will talk to you and say, ‘Mom, this and that happened at school’, or ‘Mom, can I have this or that?’ Or, ‘Mom, I learnt this at school’, or ‘Mom… we are going to a camp or museum!’ It is fulfilling. Motherhood is a very serious business, it is work, it is a duty and most importantly, it is a calling. That is why you find children who are not well looked after, you find children you would not believe live in the same home as their mother because the child is so un-attended. The mother does not care.” Gabisile (Sales Representative, 36 years old, 2 children)

A women’s social environment was a massive contributor to conceptions of motherhood. The end of Gabisile’s words above highlight another key theme: the pressure on mothers to “keep up appearances” based on the outward presentation of their children. Women felt that their mothering abilities would be directly linked to their children’s appearance – what are they wearing? What is their weight? Are they sickly or healthy? If a child does not fit the idea of what it looks like to have a mother and be mothered, a mother’s ability to care for her children is questioned.

Both in my own research and in the body of knowledge more broadly, a mother’s drive and ability to put aside their own desires and prioritise their child is generally strong and is often central to women’s experiences of motherhood. Embedded in these and other conceptions of motherhood are a commitment to sacrifice and selflessness. Mothers internalise the idea that they “should” be focused on their mothering duties, altruistic in their prioritisation of their children above themselves, and self-sacrificing to the point of personal detriment. These ideas and values can be considered positive and admirable. However, in the context of a deeply unequal society (and world), the weight of these expectations is far heavier for women in low-income settings. These women are already stretched too thin economically, emotionally, socially and physically.

It is critical that we interrogate the relative fairness and impact of these ideas and values when not all mothers are mothering from an equal footing but are striving toward the same self-sacrificing ideal. The economic and social differences between mothers in South Africa cannot be ignored, and herein lies the need to question how we can best and most fairly care for the children in our families. This question is central to the broader question of how we can best and most fairly care for all children in society, with the responsibility not falling solely on mothers or women more generally, but on the whole of a cohesive society.

In concluding, I would like to honour and acknowledge the phenomenal women I had the opportunity to interview and who made this research possible. They let me into their homes and willingly shared their often difficult lived experiences of being low-income mothers, with dignity and grace. In honour of Mother’s Day 2019, I say niyizingqayizivele! (you are one of a kind!) You have not allowed being disadvantaged by race, gender and class deter you in your invaluable but often thankless roles. Here is my ode to you:

Photo Credits:

Photo 1: Middle aged Mpondo woman on her way home (Mpande, Transkei South Afrika), 25.05.05, Marnie Knorr [reproduced under Creative Commons licensing, accessible at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mpondo_Lady.jpg]

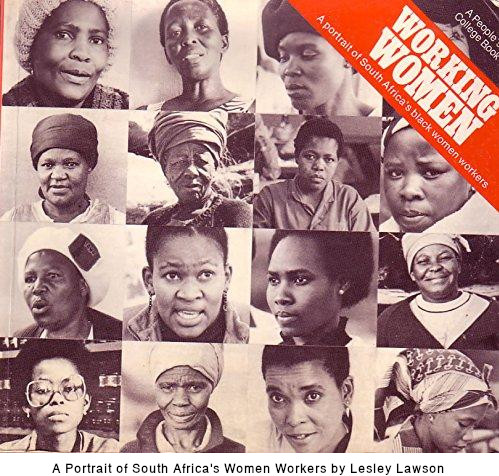

Photo 2: Lesley Lawson, 1986. "Working Women: A Portrait of South Africa's Women Workers". Johannesburg: ASached Trust/Raven Press Publication. [Photographs by Lesley Lawson]

Photo 3: Tendai Mhlanga [right to reproduce]

References:

1. Badinter, E. 1981. The myth of motherhood: An historical view of the maternal instinct. London: Souvenir Press.

2. Choi, P., Henshaw, C., Baker, S., & Tree, J. 2005. “Supermum, superwife, supereverything: Performing feminitity in the transition to motherhood”. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. Vol. 23 (2). pp. 167-180.

3. Kruger, L. 2006. “Motherhood”. In T. Shefer, F. Boonzaier & P. Kiguwa (Eds.), The gender of psychology, (pp. 182-197). Lansdowne: University of Cape Town Press.

4. Parker, R. 1996. Torn in two: The experience of maternal ambivalence. London: Viagro.

5. Phoenix, A. & Woollett, A. (1991a). “Motherhood: Social construction, politics and psychology”. In A. Phoenix, A.Woollett, & E. Lloyd (Eds.), Motherhood: Meanings, practices and ideologies, (pp. 13-27). London: Sage.

6. Hird, M. 2003. “Vacant wombs: Feminist challenges to psychoanalytic theories of childless women”. Feminist Review. Vol. 75. pp. 5-19.

7. Moore, H. 1996. “Mothering and social responsibilities in a cross-cultural perspective”. In Silva, E.B. Good Enough Mothering? Feminist perspectives on lone motherhood. London and New York: Routledge.

8. Coontz, S. 1992. The way we never were: American families and the nostalgia trap. New York: Basic Books.

9. Magwaza, T. 2003. “PERCEPTIONS AND EXPERIENCES OF MOTHERHOOD: A STUDY OF BLACK AND WHITE MOTHERS OF DURBAN, SOUTH AFRICA”. Jenda: A Journal of Cultural & African Woman Studies. Issue 4 (1). pp. 1-18.

10. Ferrant, G., Pesando, L.M. and Nowacka, K. 2014. “Unpaid Care Work: The missing link in the analysis of gender gaps in labour outcomes”. OECD Development Centre.

11. Lund, F. 2005. ‘The Totality of Women’s Work’ in M. Chen, J. Vanek, F. Lund, J. Heintz, R. Jhabvala & C. Bonner (eds.), Progress of the World’s Women 2005 (Vol. 3). Women, Work & Poverty. UNIFEM.

Author Biography

Email: nonzuzo.mbokazi@uct.ac.za