In Search of Alternative Models of Scholarship on the Mental Health ‘Treatment Gap’

Editorial Note: Sara Cooper is a Senior Scientist in Cochrane at the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC), and Honorary researcher in the Division of Social & Behavioural Sciences (DSBS) at UCT. In this piece, Sara shares some of the findings from her PhD research on the mental health ‘treatment gap’ in Africa, and the insights she has gained on further reflections of these findings since completing her PhD in 2016.

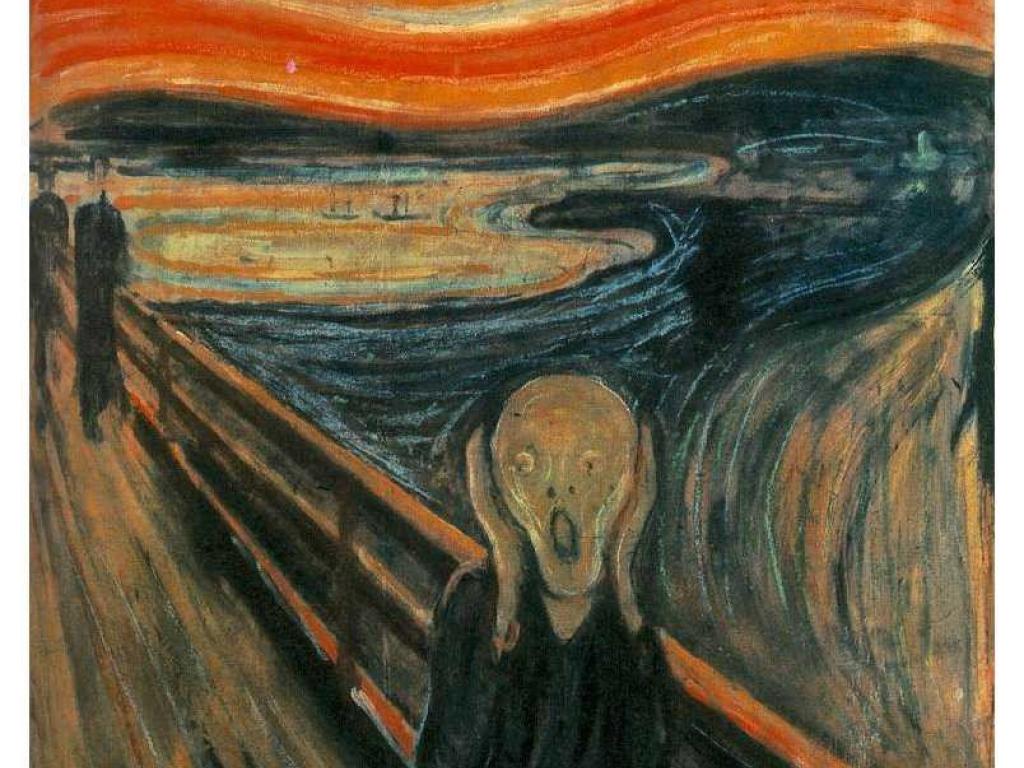

“In the late seventies I was a student of medicine and gradually got angry at the way suffering is handled in the caring professions. I realised that, basically, I wanted to react by yelling. By screaming out a revolting, inarticulate, harsh yell… Yelling, for all its loudness, doesn’t carry very far though. But what other repertoires of relating to suffering are there?” (1).

In her paper Instead of Yelling, Annemarie Mol (1) describes her early experiences of studying medicine, and her frustrations with the ways suffering was being handled. Her encounters with the caring professions made her want to respond by yelling: “By screaming out a revolting, inarticulate, harsh yell”. During my PhD research, I too so often felt like yelling. My research explored the epistemological assumptions underpinning thinking on the apparent high numbers of people with mental illness in Africa not receiving care, known as the ‘treatment gap’. That is, I was interested in the values, interests, politics and assumptions mediating knowledge produced in this area. While the conventions of meaning-making are often hidden and taken-for-granted, they help shape the kinds of questions that can be asked and thus the solutions that can be generated.

During my research, I became increasingly dissatisfied with how knowledge on the mental health ‘treatment gap’ in Africa is heavily saturated with Eurocentric tendencies, and its associated essentialised categories and rigid binary oppositions: ‘knowledge’ versus ‘belief’, ‘objective’ versus ‘subjective’, ‘traditional’ versus ‘modern’, ‘rational’ versus ‘irrational’, ‘body’ versus ‘mind’, ‘Africa’ versus the ‘West’ and so forth (2-4). However, I became equally concerned with the kinds of critiques being made against such knowledge. Such critiques suggest that Africa has its own unique knowledges and practices that are radically different from so-called ‘West, and which need to form the basis of how we understand and address the mental health ‘treatment gap’. For example, it is argued people in Africa hold traditional cultural beliefs about the causes of and treatments for mental illness, and thus supposed Western biomedical diagnostic categories and forms of care are inappropriate and irrelevant (5). Yet as I have argued, these kinds of critiques are in fact structurally very similar to the structures of knowledge they are seeking to contest. While the content may have changed, the logic has not, ultimately limiting the possibility of an effective subversion of dominant Eurocentric knowledge systems (5, 6).

Against this backdrop, here I would like to explore the following question: how we might produce alternative forms of meaning-making on the mental health ‘treatment gap’ in Africa? That is, how might we cultivate new forms of knowledge in this area which are based on alternative epistemological codes and value systems? And how might such alternatives offer potential new imaginings of public mental health critique and innovation? Seeping through the louder, master narratives of my PhD research, there were albeit softer voices that suggested certain ways in which such knowledge might potentially emerge. It is these opportunities which I wish to explore further here. Before turning to this, it is important to clarify what exactly I mean by ‘alternative’ forms of knowledge and meaning-making.

‘Alternative’ Forms of Knowledge and Meaning-making?

In line with the thinking of various Postcolonial scholars, such as Raewyn Connell and Achille Mbembe (7, 8), I understand alternative forms of knowledge as comprising new and contextually-appropriate conceptual vocabularies which are centred on local own issues and needs. Importantly, however, such knowledge needs to be predicated upon a recognition of identities and experiences as diverse, global and dynamic and which come forward as multiple forms of practices and knowledges. Thus, the development of alternative modes of scholarship is not about unearthing supposedly ‘authentic’ or ‘traditional’ forms of knowledge. Nor is it about necessarily rejecting structures of thought which might originate from the geopolitical North. Knowledge, wherever and by whomsoever it is produced, is potentially available for emancipatory and counter-hegemonic use. However, such knowledge needs to be enmeshed with the multiple local issues, needs, questions and dilemmas and be shaped by these. Ultimately, ‘alternative’ forms of scholarship are neither Afrocentric, nor Eurocentric, but ‘fit for purpose’.

What is therefore clear is that there are more ways of seeing the world and expressing it than dominant knowledge producing systems would have us believe- the messy, the complex, the contingent, the tacit, the spiritual, the associative, the experiential, the visceral, the relational.

Obviously, there are likely to be many and varied tools which might to produce such ‘alternative’ forms of scholarship, and it would be problematic to suggest that one or other is the correct one. Rather, it is about opening-up questions around what kinds of tools might hold promise for facilitating such potentially transformative models of meaning-making. Here I would like to suggest three particular tools, that emerged from my PhD research and which might provide interesting avenues for the emergence of alternative kinds of meaning-making on the mental health ‘treatment gap’ in Africa: 1) ethnographic articulations, 2) critical phenomenology and 3) ecology of knowledges.

Ethnographic Articulations: Tapping into Mess, Complexity and Heterogeneity

One important issue that emerged in my PhD research was that people’s mental health care needs and therapeutic itineraries in Africa are messy and shaped by multiple elements. Importantly, what surfaced was that the familiar kinds of measures and categories of evidence-based science are ultimately unable to capture these complexities. We thus require resources which might help us better see and think through the diverse, the fluid, the complex and the messy.

Ethnography provides a potentially promising tool in this regard. The ethnographic method, when done well, offers an important resource for imagining situated understandings and heterogeneous practices. Ethnography attends meticulously to specificities; to the apparent banality of ambivalent small things. It can foreground careful attention to the diverse and complex ways in which people make sense of daily life in the face of illness and locates such sense-making and practices within larger economic, political and historical forces. Ultimately, as a particular method, ethnography can generate a kind of complexity that rationalisation cannot flatten out or sanitise (9, 10).

However, what is at stake here is more complex than just the need for more in-depth, qualitative modes of understanding, although clearly this is required. Rather, what also matters are the underlying systems of classification which are mediating the research processes and knowledge outcomes. That is, there is a need for more careful thought around how concepts are framed, and entities are categorised. Two ethnographic studies provide important insights in this regard: Ursula Read and colleagues’ ethnographic study on the lived experiences of people with mental illness and their families living in rural communities in Kintampo, Ghana (11, 12), and Rene´ Devisch and colleagues’ ethnographic study which explored the dynamics surrounding help-seeking practices, including those related to mental health, of residents living in Kinshasa, Congo (13).

There is an urgent need to rethink how people’s needs and motivations, and the ultimate goals of care are conceptualised

In both these studies, no rigid categories were used which smoothed out paradoxes and apparent contradictions. Rather, people were represented as moving between diverse healing modalities and as holding many overlapping and seemingly contradictory priorities. The logic was one of multiplicity, with people seen to be living in a world in which both the spiritual and the scientific could be simultaneously combined. Moreover, different healing modalities were conceptualised as essentially overlapping and limited, with inevitable gaps and contradictions. These researchers thus employed what can be seen as more partial and provisional forms of categorization. And these categories were underpinned by alternative sorts assumptions about the kinds of selves, objects, and how they can be known, to those presumed in more dominant Eurocentric structures of knowledge. In resisting totalizing accounts and rigid polarisations, these two studies were able to produce understandings of the ‘gap’ in mental health care in Africa, and how it might be addressed, along alternative epistemic lines.

Critical Phenomenology: Taking ‘Other’ Epistemological Worlds Seriously

Another important issue that emerged in my research was that mental wellbeing and recovery frequently incorporate dimensions of life that are of a tacit, spiritual, emotional, and embodied nature. And as with the messy and heterogeneous, these aspects emerged as similarly not fitting easily into scientific schema. There is thus a need for tools which might help us better capture these alternative ways of knowing and being on their own terms.

Phenomenology, and in particular the more critical tradition associated with French philosopher Merleau-Ponty, might offer a useful resource in this regard (14, 15). At its most basic level, phenomenology is the study of lived experience. Adapting more traditional phenomenological strands of thought, Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology proposes a particular way of thinking about experience, and how it might be known. For him, human understanding does not consist of passive ‘thought-like’ representations, sharply delineated from ‘reality’. Rather, our sense of the world comes from the fact that we live and interact and feel and think within this world. Moreover, experience is seldom a case of individuals acting alone, but is in situation, between people and in relation to others. At the same time, experience and meaning are not solely sensory, nor intellectual, but also bodily. That is, our body incarnates our lived experiences and thus constitute our perceptual world. Finally, according to Merleau-Ponty, lived experience inevitably transcends our capacity to fully know and understand. In other words, our involvement with, and understanding of, the world is continually emerging or ‘becoming’, and thus always somewhat incomplete, temporal and indeterminate.

Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology thus represent an alternative kind of conceptual framework to more dominant, Eurocentric ones. No rigid polarizations are constructed, but rather existence and understandings are conceived of as “both intentional and bodily, both sensory and motor, and so neither merely subjective nor objective, inner nor outer, spiritual nor mechanical” (16). As such, his philosophy opens-up the space for ways of knowing and dimensions of life that go against the totalizing grain- the bodily, the sensorial, the emotional, the sacred. Moreover, this understanding of existence being a space of ‘inter’ resonates with conceptions of identity in Africa which often emphasise relatedness rather than individuality (17). Finally, at the heart of Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology is the value of genuinely acknowledging our gaps in understandings, which interferes with the kinds of certainties so embedded in Eurocentric systems of knowledge.

As part of my research, I spoke to about 30 psychiatrists working in public sector settings in South Africa, Nigeria, Uganda and Ethiopia. As I have demonstrated elsewhere (4), some of these psychiatrists appeared to be operating within this critical phenomenological tradition associated with Merleau-Ponty (4). In undertaking the kind of ‘practical relativism’ associated with phenomenology, these psychiatrists were able to tap into and appreciate, the many personal, emotional, moral, spiritual and socio-cultural priorities of their patients. Moreover, these psychiatrists consistently acted against the rationalist fantasies of biomedicine, genuinely recognizing and incorporating into their practices, the inevitable partialness of biomedical science.

In appreciating the diverse and complex nature of human beings, and the limits of biomedicine, these psychiatrists seemed to be producing alternative forms of knowledges and practices on the mental health ‘treatment gap’. For them, there is an urgent need to rethink how people’s needs and motivations, and the ultimate goals of care are conceptualised in the first place. Moreover, according to them, addressing the ‘gap’ in mental health care necessitates better understanding, and potentially learning from, ‘other’ healing systems which may be based on different kinds of epistemologies to biomedicine. And for these psychiatrists, there is a need for greater humility on the part practitioners. That is, it is important for service providers to cultivate a particular way of being, one which engenders greater uncertainty and less conviction. So, what these psychiatrists were articulating is that thickening our knowledge and associated practices around the ‘gap’ in mental health care should be about less and not more, perhaps paradoxically, it is about fostering a gap in knowing. Ultimately, it is through this uncertainty that a space is potentially opened for new forms of thinking and alternative sorts of practices to grow and become part of the clinical exchange.

Moving From a Knowledge Monoculture to an Ecology of Knowledge

What is therefore clear is that there are more ways of seeing the world and expressing it than dominant knowledge producing systems would have us believe- the messy, the complex, the contingent, the tacit, the spiritual, the associative, the experiential, the visceral, the relational. If these other ways of knowing and being are to possess any kind of power and influence, then something profound needs to change within the centres of power themselves, and not just at the margins. That is, the canon of academic knowledge needs to be more democratic, epistemologically inclusive and more “hospitable” to different iterations of reason and the reasonable (18).

The creation of a more open and hospitable knowledge archive is, however, a slippery task and inevitably faces the now widely debated issue of relativism. That is, do appeals to knowledge diversity and inclusivity open the floodgates? Do we now live in a relativist world? Relativism is not a good option. Within the context of very real mental suffering and limited healthcare resources, the dangers of taking a relativist stance are manifold. Relativism may also be somewhat of an epistemologically suspect position. For example, Donna Haraway (19) sees relativism as the “the perfect mirror twin of totalization in the ideologies of objectivity”. According to her, relativism and universalism “are both ‘god-tricks’ promising vision from everywhere and nowhere equally and fully…both deny the stakes in location, embodiment, and partial perspective; both make it impossible to see well”.

Thus, instead of accepting a single and transcendent rationality or being reduced to a feeble form of relativism, it is about taking as a question of research how we can work credibly, critically and ethically with diverse knowledge systems. That is, it is about fostering an intellectual project which engages with how we might rethink and rekindle the capacity to test knowledge and ways of knowing which do not straightforwardly disqualify nor valorise whatever does not fit the epistemological canon of science. This kind of knowledge project is, however, almost non-existent within public (mental) health. And yet if we are to develop alternative models of scholarship on the mental health ‘treatment gap’ in Africa, greater thought is required around how this kind of intellectual project might be nurtured.

Conclusion

Let us end by returning to Mol and her yelling. Despite her immense frustration at the caring professions, she concedes that “Yelling, for all its loudness, doesn’t carry very far” and poses the question “But what other repertoires of relating to suffering are there?”. Here I have suggested three particular methodological tools that comprise ‘other repertoires’ and which might provide opportunities for new imaginings and understandings of the ‘gap’ in mental health care in Africa.

Most certainly, current demands of the global knowledge economy pose several limitations for alternative forms of meaning-making to grow and to enter into sites of potential power and influence. Economies of scale in government, in decision making by policy-makers, in assessments by donor agencies increasingly depend upon uncontroversial, policy-relevant forms of knowledge which are based on replicable methodologies and categorical schemas. Many of the problematic features of knowledge on the mental health ‘treatment gap’ are precisely those which make them attractive to governments and donor institutions. And novel research and practice-based approaches to mental health care often struggle to attract research funding. As such, asking current seats of power to better live with, and think in, the provisional, the heterogeneous, the complex, and the ambivalent, may be a tall, if not naïve order.

However, if the mental health needs and wants and desires, and associated practices, of people in Africa are only talked about in terms that are not relevant to their specificities and diversities, they will be submitted to regulations and rules that are foreign to them. Ultimately, as suggested by Mol and colleagues “This threatens to take the heart out of care- and along with this not just its kindness but also its effectiveness, its tenacity and its strength” [20]. There is thus an urgent need for boundary pushing within the modes of knowledge production on the mental health ‘treatment gap’ in Africa. While such boundary pushing is likely to be an uphill struggle, its potential to nurture alternative forms of meaning-making and interventions I am convinced makes it worth the trouble.

References

1. Mol, A., Instead of yelling: On writing beyond rationality. . EASST Review, 2001. 20(2): p. 3-5.

2. Cooper, S., Prising open the 'black box': An epistemological critique of discursive constructions of scaling up the provision of mental health care in Africa. Health (London), 2015. 19(5): p. 523-41.

3. Cooper, S., Beneath the rhetoric: Policy to reduce the mental health treatment gap in Africa. Disability and the Global South, 2015. 2(3): p. 708-732.

4. Cooper, S., "How I Floated on Gentle Webs of Being": Psychiatrists Stories About the Mental Health Treatment Gap in Africa. Cult Med Psychiatry, 2016. 40(3): p. 307-37.

5. Cooper, S., Research on help-seeking for mental illness in Africa: Dominant approaches and possible alternatives. Transcult Psychiatry, 2016. 53(6): p. 696-718.

6. Cooper, S., Global mental health and its critics: moving beyond the impasse. Critical Public Health, 2016. 26(4): p. 355-358.

7. Connell, R., Southern theory: The global dynamics of knowledge in the social sciences. 2007, Sydney: Allen and Unwin.

8. Mbembe, A., African modes of self-writing. Public Culture, 2002. 14(1): p. 239-273.

9. Chua, L., C. High, and T. Lau, Introduction: Questions of evidence., in How do we know? Evidence, ethnography, and the making of anthropological knowledge, L. Chua, C. High, and T. Lau, Editors. 2008, Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Cambridge. p. 1-19.

10. Strathern, M., Old and new reflections, in How do we know? Evidence, ethnography, and the making of anthropological knowledge, L. Chua, C. High, and T. Lau, Editors. 2008, Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Cambridge. p. 20-35.

11. Read, U., "I want the one that will heal me completely so it won't come back again": the limits of antipsychotic medication in rural Ghana. Transcult Psychiatry, 2012. 49(3-4): p. 438-60.

12. Read, U.M., E. Adiibokah, and S. Nyame, Local suffering and the global discourse of mental health and human rights: an ethnographic study of responses to mental illness in rural Ghana. Global Health, 2009. 5: p. 13.

13. Devisch, R., et al., A community-action intervention to improve medical care services in Kinshasa, Congo. , in Applying health social science: Best practice in the developing world, H.N. Higginbotham, R. Briceño-León, and N.A. Johnson, Editors. 2001, Zed Books: London, UK. p. 107-140.

14. Merleau-Ponty, M., The world of perception. 2004, London: Routledge.

15. Merleau-Ponty, M., The phenomenology of perception. 1962, London, UK: Routledge.

16. Carman, T., Merleau-Ponty. 2008, New York, USA: Routledge.

17. Nyamnjoh, F., ‘A child is one person’s only in the womb’: Domestication, agency and subjectivity in the Cameroonian grassfields, in Postcolonial subjectivities in Africa, R. Werbner, Editor. 2002, Zed: London, UK. p. 111-138.

18. Green, L., Challenging epistemologies: Exploring knowledge practices in Palikur astronomy. . Futures, 2009. 41: p. 41–52.

19. Haraway, D.J., Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. , in The science study reader, M. Biagioli, Editor. 1999, Routledge: New York, USA. p. 172-188.

20. Mol, A., I. Moser, and J. Pols, Care in practice: On tinkering in clinics, homes and farms. 2010, London, UK: Transaction Publishers.

Author Biography

Email: Sara.Cooper@mrc.ac.za