Personal Protective Equipment for Tuberculosis Infection Prevention and Control in the Western Cape: Disjunctures Between Policy and Practice

Idriss Kallon

Editorial Note: Idriss Kallon works as a Research Assistant on Umoya Omuhle, an interdisciplinary research project about tuberculosis infection prevention and control in primary health care settings in the Western Cape and KwaZulu-Natal provinces in South Africa. The project is a collaboration between the Division of Social and Behavioural Sciences at UCT, the University of KwaZulu-Natal, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (UK), and Queen Margaret University (UK). In this piece, Idriss shares some early findings from HCW narratives and his own personal reflections on conducting research in high TB prevalence clinic spaces.

Tuberculosis Infection and Personal Protective Equipment

South Africa has an extremely high incidence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB) with 834 cases per 100 000 people, compared to 195/100 000 in other high burden countries (1). Although treatment has evolved and improved, there are ongoing problems with access and adherence and drug-resistant TB (DR-TB) has also become an urgent public health problem. South Africa also has a high DR-TB prevalence, which contributed to the 600,000 cases observed globally in 2016. In the same year, 190,000 people died from DR-TB (2). Healthcare workers (HCWs) are three times more likely to contract TB than the general population, and nurses (“frontliners” who work closely with infected patients in clinics) are particularly at risk (2-4). Patients awaiting consultation or treatment for other reasons are also at high risk of contracting TB in the clinic space. The use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) is one of the mainstays of infection prevention control (IPC) and its importance is embedded in global, national and local policies (5-7). PPE is also important for preventing many other nosocomial infections (diseases that are contracted when hospitalised or when accessing a health centre for services). PPE involves wearing respirator masks in clinics, wearing gloves while treating certain patients, regular hand-washing, and the use of hand sanitizers before and after treating patients, as well as a number of other strategies.

Umoya Omuhle

Umoya Omuhle (“fresh air”) is a research collaboration between the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Queen Margaret University, the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN), and the University of Cape Town (UCT). It uses an interdisciplinary, “whole-systems” approach to study nosocomial transmission of DR-TB and IPC implementation in two South African provinces (the Western Cape and KwaZulu-Natal). The longer-term hope is that a better understanding of these factors may help in identifying ways of minimising DR-TB transmission. A whole-systems approach involves consideration of the various (social, biological and infrastructural) factors that might affect IPC. In this case, we are reviewing the macro context by trying to map the influence of historical global and national IPC policies. At the meso-level, we are considering healthcare settings in detail – the design of the clinic, how TB care is organised, and the management culture observed at clinics (12). Finally, at the micro-level, we will explore the daily practices in clinics, as well as HCWs’ perceptions of their own risk and how they understand their responsibility for implementing IPC (12).

Upon my appointment as a research assistant on this project, there was much discussion about our own use of PPE when conducting research in the field. With the high prevalence of DR-TB in mind and the many discussions about respirators and surgical masks, we knew we were at risk and needed to have access to the appropriate protective equipment. Based on field experiences in six clinics offering decentralised TB and DR-TB treatment in the Western Cape, this article reflects on conversations with key informants and HCWs to describe some of the problems associated with the use of respirators and surgical masks in health settings, and to highlight the disparities between policy and practice. I also offer some personal reflections on my own field experiences. Although the South African government’s policies on TB IPC borrow from global policies and reflect best practices (2,5-8), there are ongoing issues with implementation that result in gaps between policy and practice, with worrying implications for minimising infection.

IPC Measures and PPE’s Hidden Messages

It is clear that the protective paraphernalia used by HCWs sometimes carries subliminal messages. Despite their importance for preventing infection, interpretations of the meaning of respirators, surgical mask or gloves is context-specific and varies from place to place. For example, although wearing gloves and masks during an outbreak like Ebola was critical in curbing the highly contagious and deadly pandemic, it was also alienating for those who were trying to access care and may have made them unwilling to talk to HCWs (9). In other settings, such as primary care clinics in South Africa where TB is normalised due to its high prevalence but may still have fatal consequences if contracted, the use of gloves and masks is important but also carries stigma (11). This is particularly apparent in the case of the N95 respirator mask, a key IPC tool that has been proven to prevent the contraction of TB and other respiratory infections (10, 13-15). As visible in the pictures below, the N95 mask is noticeably different from the “regular” surgical mask worn by patients. The N95 is only used by HCWs and visitors in the clinic and can attract attention from patients.

As researchers, we also felt the distancing effects of wearing PPE. We were instructed to use our N95 respirators during all of our interviews. In two of the (rural) clinics we worked in, not one staff member nor patient wore a N95 respirator or a surgical mask. We walked between people in the waiting room, writing on our notepads as we observed the clinic infrastructure. It felt very uncomfortable. In one of the clinics, a patient even walked up to me and asked me why I was wearing the N95 respirator. I told her I wanted to protect myself from contracting TB. She then asked if they (the patients) were also at risk of contracting TB because no one had told them to wear a mask. Our equipment for TB protection was clearly transmitting hidden and unintended messages. In trying to draw further conclusions, we observed the following two scenarios at clinics. Sometimes patients were told to wear the surgical mask but chose not to. Other times, patients were never told to wear a mask, or informed of the risks of not wearing one. We also noticed that patients who wore their surgical or “regular” masks did not wear them consistently, either because they did not know how to or because they were worried about stigma.

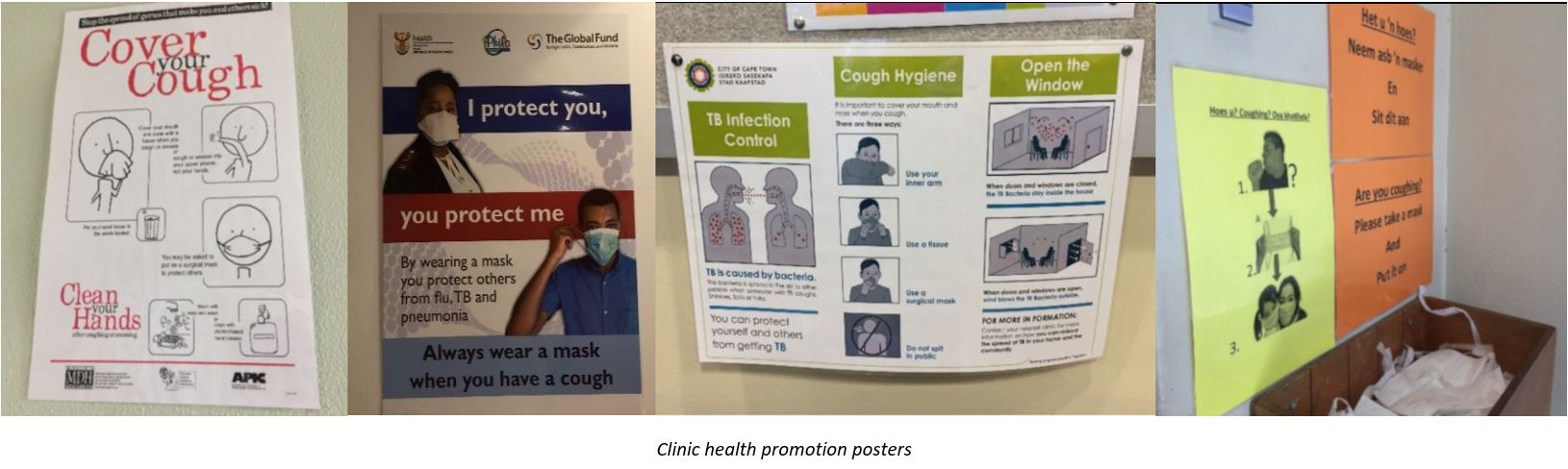

In addition to exploring whether and how HCWs adhered to PPE, we also observed attempts to implement a series of administrative, managerial and environmental measures to prevent or limit infection in healthcare facilities. Current World Health Organisation and other global policies suggest that although PPE is a critical measure in TB IPC, it should ideally be used in conjunction with these other measures or at worst, as a backup if these other control measures fail (5,6). In our work thus far, we observed efforts at implementing IPC measures including proper screening and triage of new patients, tailoring the appointment system according to certain categories of patients, managing patient congregation and patient flow, and reducing waiting times. However, we also observed many cases of lapses in these administrative, managerial and environmental control. For example, although there were sometimes posters on the walls that informed patients to cover their mouths when coughing, clinics often did not explicitly explain “cough hygiene” to patients. Some patients who could have been infectious moved freely from one area of the clinic to the other, not all patients were screened for TB upon entering the clinic, and some patients with appointments waited even longer. There also seemed to be managerial confusion, with clinic managers suggesting that the rationale for appointment systems was to minimise inconvenience for patients rather than to reduce the chances of infection with TB or another communicable disease.

HCWs Perspectives on PPE, IPC and Perception of Their Own Risk

Below, I share HCW perspectives regarding PPE, IPC more broadly, and perception of their and others’ risk of contracting TB. Obtaining and learning from HCW perspectives is an important aspect of designing contextually-relevant strategies for supporting IPC, and for ensuring these are appropriately implemented. One of the many concerns that a key informant raised was the passive approach to curbing occupationally-acquired TB in tertiary hospitals. During his training as a medical intern, he had noticed that training doctors working in tertiary hospitals did not seem very interested in infection control nor in adhering to PPE based on the norms and cultural milieu in which they worked and were trained:

…the standing joke was that you will breathe in TB the moment, the first time you step into the hospital. It's inevitable, everyone there has TB infection, but don't worry, you are young and healthy and on a higher socio-economic class, you won't get sick

The same key informant talked about a close relative who had been diagnosed with MDR-TB and some of his colleagues being infected with TB during their medical internship and training at a hospital in the Western Cape:

…[as a paediatric surgeon] my wife… [contracted] multi-drug resistant TB…. [In my] final year, two of my friends got TB… But still, you kind of put it in a different box because you're too busy trying to get the degree and [get] the work done as a junior doctor.

Over time (possibly as a result of infection among friends and family), he and other medical students became enthusiastic about bringing PPE to the fore in hospital IPC policies. They had noticed the lack of policy initiatives around occupationally-acquired TB and worked hard to ignite debates around the availability and effective use of N95 respirators.

Another key informant echoed this suggestion that more attention be paid to occupationally-acquired TB by means of PPE. However, he seemed confused about the importance of the respirator mask and rather than emphasising the importance of using both PPE and other measures to prevent nosocomial infection, he implied that when administrative controls are in place the use of masks is optional.

The respirators are to prevent people being infected. So, who do you put those on if you're dealing with a known TB case? …. And if they're drug sensitive and they've been on [treatment] for a month, why are you wearing it? …. there's a lot of confusion in people's minds between masks and respirators …and then it becomes a disciplinary issue, ‘why aren't you wearing a mask and respirator?’ So administrative [control] is [supported by] the strongest evidence…from the US… [although it] was a very different setting… by the… 60's they claimed that they had eliminated [TB] by testing patients, by having a barrier at the front doors where they test patients with TB, and [by] treating them.

Apart from confusion about who should wear the respirator or surgical mask at any given time, the general assumption was that HCWs do not feel that their risk of contracting TB is high and thus, do not wear respirators. We heard nurses say that as they had been working in the clinics for many years and had not contracted TB, there was no need to wear masks. Similarly, a key informant from the Western Cape Department of Health said,

… staff feel that their risk is very low… so low that they don't need to take extra precautions. If you go into facilities, you'll find staff wearing [surgical] masks that are not providing any protection, or not wearing masks at all. You'll find staff wearing [respirator] masks during the quality assurance assessments and things like that …the rest of the time, if you walk in there - I mean, for all the years that I’ve been working and dealing with TB facilities I was never asked, I was never offered a [respirator] mask.

HCWs felt that the need for wearing a mask was dependent on what kind of work they did, where they worked in the clinic, or how comfortable the mask was. For example, a clinic manager said, “…we don’t wear any mask on the other side (non-clinical spaces). Only the TB staff are wearing the mask”. Another HCW explained that, “I'm sure that if you go into the TB area now people will be wearing their masks etc. I, on the other hand I have a physiotherapy background… so when I go into the areas [where TB patients are treated] I don't [wear a mask]- and I’m not ill, I don't wear a mask. Because I trust the ventilation system, the fresh air and the natural light”. Finally, another clinic manager explained the reasons for not wearing masks as a “personal thing”:

…maybe it smells funny or they can't breathe… [or] the fit. Yeah that is the problem. Others say [that] when they are seeing patients in the TB room [is when they wear the N95 mask]. But other than that, you won't find them wearing masks. I think… it's also the discomfort from wearing a mask….

Clinic managers not only admitted that they were not using the mask but required more evidence to motivate other HCWs to wear respirators in the clinic. We were unsure if they had access to the available research or policy.

Final thoughts

Nosocomial transmission of TB is on the rise in South Africa and will require a signification allocation of the government budget on health. Evidence shows that HCWs are three times more likely to contract TB because they are the frontline of infection. In addition, we know that global and local policies affirm the use of PPE to help prevent TB infection in health facilities alongside administrative and environmental controls. However, HCWs we talked to were sometimes unaware of how to use the masks, were concerned that they may alienate patients, or were not properly informed about their risk. Managerial staff also seemed ill-informed, and patients were under-educated about the importance and proper usage of PPE. These problems are compounded by misunderstanding or confusion about why administrative, environmental and managerial policies have been introduced, resulting in poor implementation. The policy/practice disjuncture regarding the use of respirators is a cause for concern.

Further research is needed to better understand the implications of this disjuncture and to produce context-specific recommendations about the best way forward. It is possible that being proactive in motivating for the consistent use of respirators and strengthening the other aspects of IPC could enable greater adherence to TB IPC in primary healthcare clinics. Improvements might include managing the appointment system to decrease the patient flow at a given time, managing patient congregation in certain areas, and reducing the waiting time of patients who could potentially be spreading TB in the facility. At the very least, there is a need for more commitment to awareness-raising and closing the gaps in the implementation of proper PPE, as well as the necessary administrative, managerial and environmental prevention and infection control measures.

References

1. World Health Organization (WHO). 2017. Global tuberculosis report 2016. Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/250441/1/9789241565394âeng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 11 March 2019.

2. Engelbrecht, M., Janse van Rensburg, A., Kigozi, G & van Rensburg, HCJ. 2016. Factors associated with good TB infection control practices among primary healthcare workers in the Free State Province, South Africa. BMC Infectious Diseases. 16(633): 1-10.

3. Schmidt, B., Engel, M.E., Abdullahi, L & Ehrlich, R. 2018. Effectiveness of control measures to prevent occupational tuberculosis infection in healthcare workers: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 18(661):1-12.

4. O’Hara L.M., Yassi, A., Zungu, M., Malotle, M. Bryce, E.A., Barker, S.J., Darwin, L & FitzGerald, J M. 2017. The neglected burden of tuberculosis disease among healthcare workers: a decadelong cohort study in South Africa. BMC Infectious Diseases. 17. (547): 1-11.

5. World Health Organisation (WHO). 2009. WHO Policy on TB Infection Control in Health-Care Facilities, Congregate Settings and Households. Geneva: WHO.

6. World Health Organisation (WHO). 2016. Guidelines on Core Components of Infection Prevention and Control Programmes at the National and Acute Health Care Facility Level. Geneva: WHO.

7. National Infection Prevention and Control Guidelines for TB, MDR-TB and XDR-TB, 2015. Pretoria: Department of Health.

8. Zinatsa, F., Engelbrecht, M., Janse van Rensburg, A & Kigozi, G. 2018. Voices from the frontline: barriers and strategies to improve tuberculosis infection control in primary health care facilities in South Africa. BMC Public Health 18:(269): 1-12.

9. Nuriddin, A., Jalloh, M.F., Meyer, E., Bunnell, R., Bio, F.A., Jalloh, M.B., Sengeh, P., Hageman, K.M., Carroll, D.D., Conteh, L & Morgan, O. 2018. Trust, fear, stigma and disruptions: community perceptions and experiences during periods of low but ongoing transmission of Ebola virus disease in Sierra Leone, 2015. BMJ Global Health. 3: 1-11

10. Qian, Y., Willeke, K., Sergey, A., Grinshpun, D J & Coffey, C. 1998. Performance of N95 Respirators: Filtration Efficiency for Airborne Microbial and Inert Particles. American Industrial Hygiene Journal. 59 (2):128-132.

11. Abney, K. 2018. “Containing” tuberculosis, perpetuating stigma: the materiality of N95 respirator masks. Anthropology Southern Africa. 41.(4):270-283.

12. Umoya Omuhle: Policy, Systems, and Organisation of Care for TB Infection Prevention and Control in KwaZulu-Natal and Western Cape, South Africa. 2017. Project Research Proposal. Also see link for more info: https://www.lshtm.ac.uk/research/centres-projects-groups/uo

13. Biscotto, C. R., Pedroso, E.R.P., Starling, S.E.F & Roth, V.R. 2005. Evaluation of N95 respirator use as a tuberculosis control measure in a resource-limited setting. International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 9(5): 545-549.

14. Chughtal, A.A & Khan, W. 2019. Use of personal protection equipment to protect against respiratory infections in Pakistan: A systematic review. Journal of Infection and Public Health. 1024:1-6.

15. Rengasamy, S., Shaffer R., Williams, B & Smit, S. 2017. A comparison of facemask and respirator filtration test methods. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene. 14 (2): 92-103.

Author Biography

Idriss Kallon holds a BA in History and Sociology from the University of Sierra Leone, an Honours in Development Studies at the University of Cape Town (UCT), and a Master's in Environmental Health from Cape Peninsula University of Technology. He was an Education Development Teaching Assistant in the Sociology Department at UCT from 2014-2018. He completed his PhD in Public Health in 2018. His research explored continuity of care for TB patients discharged from tertiary and district hospitals in South Africa.

Email: idriss.kallon@uct.ac.za