Coming of Age in Khayelitsha: Lessons on Certainty and Privilege

Lauren Greenwood (BSc Student, UVA)

Editorial Note: Lauren Greenwood is an undergraduate student in Human Biology at the University of Virginia. She has spent two summers working with Division staff and students on various projects with members of the Town Two community in Khayelitsha.

Coming to the Field

Bleary eyed from twenty-four hours of travel, disoriented, and hungry, I arrived in Cape Town in May 2017 suddenly all too aware of two facts: I was very far from home and only knew one other person on the same continent. Nerves aside, I came as an idealistic and eager twenty-year-old. After spending the past year in the classroom learning about social determinants of health and community engagement, I came to Cape Town ready to “do” public health and participate in UVA’s Field School for Public Health Research Methods.

Within my first few days in South Africa, my academic mentors and field guides introduced me to Khayelitsha, where the Field School, a field-based research methods training for UVA students supported by DSBS staff and students, would be based. On the outskirts of Cape Town, Khayelitsha was created by the apartheid government on undesirable land far from the city centre to house black South Africans meant to serve as labourers for the white population of the city (1). Still majority black and in struggling with poverty, about 20% of the Cape Town population now calls Khayelitsha home (2); most living in cinder block and brick structures surrounded by informal settlements of shacks.

Khayelitsha, as the place where their life was currently playing out, had a contradictory role in their lives. It was a part of their identity, a place that housed family, Xhosa culture, and knowing how to have fun. It also, however, was the place that housed their hardships: the lack of jobs, the lost sense of purpose, the appeal of crime, and the consequences of corruption.

Over the course of five weeks, I began to develop my own understanding of Khayelitsha. In Khayelitsha, structural violence, the social, economic, and political configurations of the world that put certain individuals and populations in harm’s way, was palpable (3). People there, however, did not let this precarity define them but rather found ways to create hope and opportunities where little was evident. During my time there, I had to learn how to talk and relate across layers of difference: culture, skin colour, age, nationality, and socioeconomic status, and quickly discovered the challenges of this task. This is what drew me back to Khayelitsha and Cape Town for a second summer. I felt like my eyes had begun to open, and I wanted to continue to see more deeply.

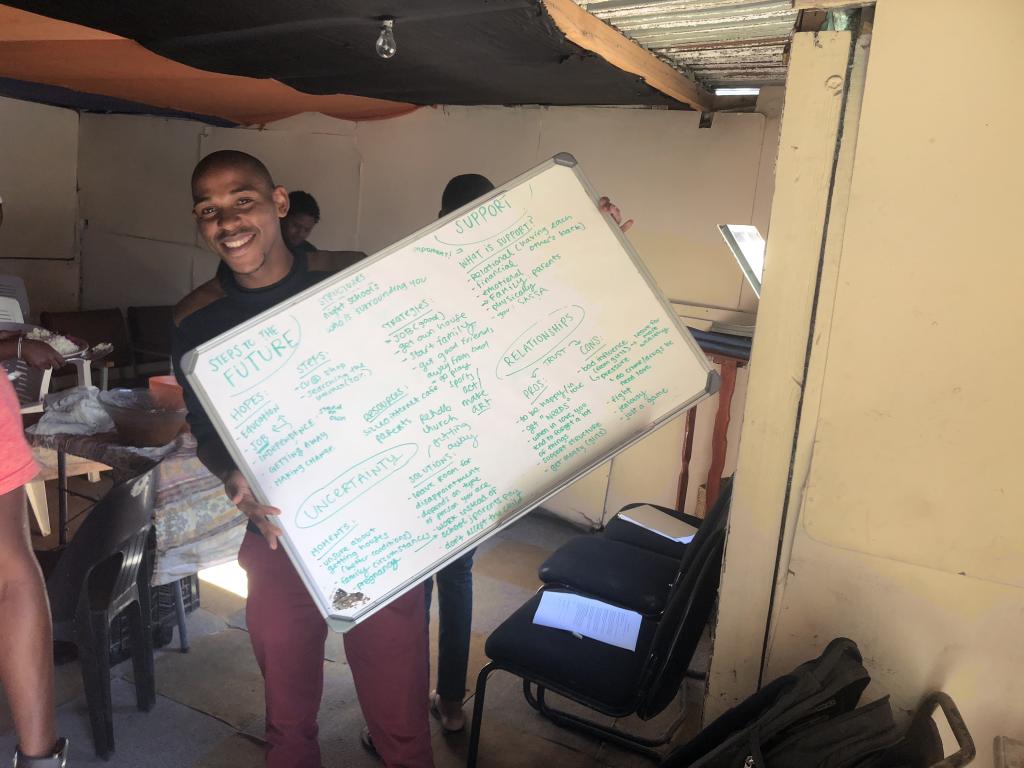

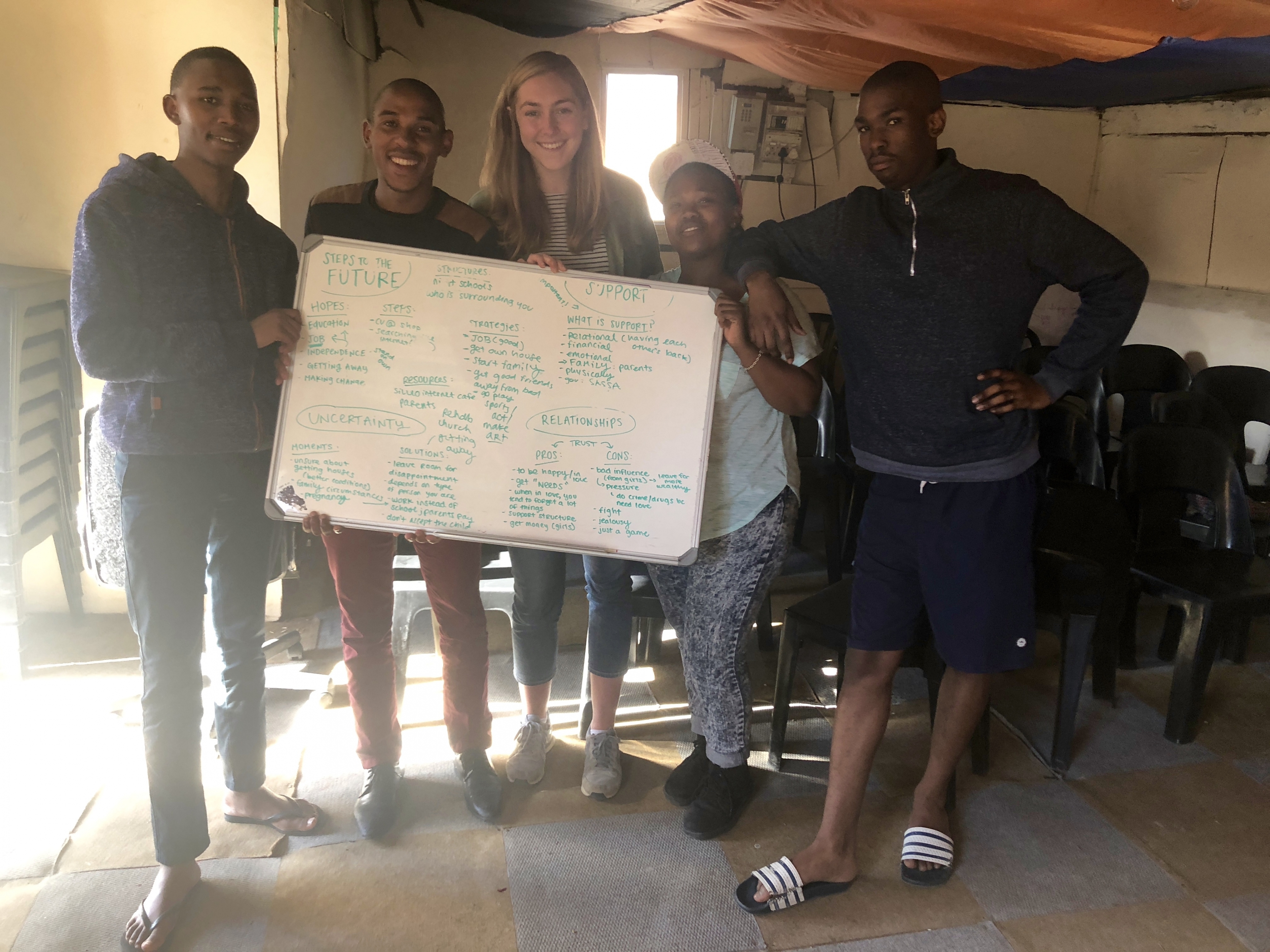

In my second trip to South Africa, I conducted an independent research project under the guidance of Alison Swartz, Chris Colvin, and Zara Trafford. Qualitative and ethnographic, my research looked at how young people in socially marginalised positions imagine and work towards their future given the uncertainty of their circumstances. No longer surrounded by a horde of other students and professors, my focus group discussions were largely just me and my research partners. Often times, our conversations resembled those of any other group of twenty-somethings grappling with questions of entering into adulthood. In the following sections, I present some of my findings related to coming of age in Khayelitsha for those who live there, but also what coming of age in this context has meant for me.

Coming of Age: Residents

Young black South Africans growing up in a township setting like Khayelitsha face a variety of complicated and intersecting challenges, such as a high rate of HIV and TB (4), a high rate of unintended and teenage pregnancies (4), and a high rate of unemployment (5). While in principle, their opportunities may seem much better than those available to older generations under apartheid, many young black South Africans still have limited access to basic services like health care, education, and employment, limiting the reality of these the celebrated opportunities of life after apartheid (6). Many avenues through which adulthood is traditionally established, like marriage or moving out of the parental home, remain out of reach for these youth. While uncertainty defines much of their existence, many have found ways to become creative agents, establish themselves, and work towards the future in this space.

The way that the young people I spoke to envisioned their future and the routes to achieving that future resembled more of a mosaic of shifting strategies rather than a singular, sequential life path. The young people I spoke with desired a future that was more secure than their present circumstances and used a combination of strategies that were fluid, dynamic, adaptable, and often contradictory as the best way to get there. Young people commonly incorporated obtaining an education, getting a job, being a “good” person, moving, being in a relationship, making a change in the community, and gaining independence into their set of life goals and strategies. These approaches were often included because of the opportunity they in themselves represented and their ability to provide access to further opportunities and a surer future. While what an individual chooses to weave together often changes, there were factors that seemed to influence which particular strategies an individual chose to employ in a particular moment.These factors, discussed below, included gendered pressures and expectations, articulating success through self-reliance, and status symbols of mobility.

Gendered pressures and expectations

Gendered pressures and expectations often shaped young people’s desires and actions. Young men often spoke of feeling pressure from young women, family members, and other men in the community to prove different aspects of their masculinity. They regularly said that their girlfriends would leave them for a wealthier man if they were not providing for her. In their minds, young women wanted money, young men wanted love, and because of this tension and the limited employment opportunities, young men were often led into crime. Family was an additional source of pressure for young men, as they felt it was their duty to get a job or an education to provide for their family members. They particularly felt the need to provide for younger sisters in order to ensure that the young girls did not turn to a “blesser” or sugar daddy for support. Finally, young men often felt compelled by other men in the community, both elders and peers, to have multiple girls to prove their masculinity and their “qualifications” for marriage. The case of young men shows how in the absence of many other opportunities, forging an identity through sexual partnerships takes on increased importance. This statement applies to the situation of young women in Khayelitsha as well. The young women with whom I spoke wanted to and felt pressure to be a 'modern woman', who had many material goods, an education, and equality in their potentially multiple sexual and romantic partnerships. Many, however, found pursuing and managing these desires hard to achieve in reality, when support from family can be limited and young motherhood can be viewed as incompatible with school.

With so many of my focus groups discussions centred on uncertainty, I quickly began to understand that certainty was a luxury item reserved for the privileged.

Striving for self-reliance

In a context of limited resources, many young people took on a stance of self-reliance. While the external world remained uncertain and precarious, success was often articulated through their “internal world,” making statements like, “you don’t have to depend on something. The thing is in you.” They provided many examples of how external systems had failed them, whether friends turning their backs, parents not being able to provide financially, or corruption in the government leaving promises unfulfilled. In this environment of uncertain support, looking inward and developing resources within yourself to draw upon, such as self-discipline, perseverance, and strong morals, was a way of providing certainty, resiliency, hope, and direction for the future. Additionally, speaking about the “unlimited potential of humans” was an assertion of individual agency and a way to make more feel possible and no barrier too big.

Mobility

Conceptualisation of and movement through spaces also played a large role in how young people pictured their future. When asked what they thought of different places, young people often described Khayelitsha as a place of boredom, challenges, blackness, family, distrust, and fun. Khayelitsha, as the place where their life was currently playing out, had a contradictory role in their lives. It was a part of their identity, a place that housed family, Xhosa culture, and knowing how to have fun. It also, however, was the place that housed their hardships: the lack of jobs, the lost sense of purpose, the appeal of crime, and the consequences of corruption. In contrast, the city centre of Cape Town was seen as a place of jobs, modernity, and resources, Johannesburg as a place of opportunities and new faces, and the suburbs as a place of safety and whiteness. These places were largely places where young people wanted their future to occur. While less accessible, these were spaces in which one could achieve success and security.

In the absence of the ability or opportunity to get to these spaces that they see as “better place[s] to stay,” young people often pursue symbols that have ties to these places or that suggest they could get there. For young men, this typically takes the form of a car, while for young women, this could be long fake eyelashes, cell phones with airtime, or specific shoes. For many young people, these symbols are an avenue through which they construct an identity of success and adulthood in their present circumstances. These symbols become a manifestation of young people’s agency and ability to get outside the structural presence of poverty in Khayelitsha.

Coming of Age: Outsider

While I felt my eyes had been opened in the course of my first trip to Cape Town, this last year was when things really took hold. I came to Cape Town idealistic and empathetic, wanting to do good in the world but not sure quite how. My two summers in Cape Town disillusioned me in the best way possible. I had to learn and am still learning how to live, interact, and engage with open eyes in a world that can be good and very problematic at the same time.

I knew I was privileged before going to Cape Town – I grew up comfortably, my parents both graduated from university and were always stably employed, and I could afford to study abroad in Cape Town. I was not, however, aware of how deeply privilege was engrained in my life. With so many of my focus groups discussions centred on uncertainty, I quickly began to understand that certainty was a luxury item reserved for the privileged. For example, one of the young men I befriended this past summer wanted to become a cardiologist. While I loved his spirit and talking about medicine with him, I wrestled with how difficult it would be for him to actually realise this goal and become a physician when some of the schools in the area did not have a consistent math or science teacher for Grade 12.

After our chats, I often would reflect on my own path towards medicine. While I have worked very hard to get to where I am of being accepted into medical school, there are a lot of certainties provided by the safety net of privilege underlying my journey – my high school offered Advanced Placement courses for university credit, I went to university, and I could afford to stay in school for the many years required to become a doctor, not needing to leave or change fields for a quicker financial payoff. At any point, if I do not become a doctor, it would be because I changed my mind, not because of structural forces barring me from that opportunity.

My second year in Khayelitsha, I felt that people were more open with me about their lives and vulnerable about the struggles they faced. While it was beautiful to be ‘let in’ like this, it also brought challenges. One Sunday, I went to a local church in Khayelitsha with a few people I had come to know over both years. It was a very joyful experience, but at the same time, there was a lot of underlying sorrow. I heard stories of what it was like to live in a shack during the winter, and I would look outside the church to see lines of people collecting muddy water with buckets. This was one of the times when I felt defeated; like structural violence was a boulder I was trying to chip away at but would never really move. While this was very difficult for me to handle emotionally, I also saw the resiliency and spirit that existed in these communities and was encouraged to use experiences like these as motivation. I eventually hope to have a career in medicine and global health, making health care work better for populations like those of Khayelitsha, and as I continue on in my journey, I will bring these stories, moments, and friendships with me letting them continually guide and shape me.

In a commencement speech titled This is Water, David Foster Wallace discusses how gaining an education is not per se about gaining knowledge, but more about learning how to think (7). Wallace emphasises that we must make the conscious decision about how to think and what to pay attention to (7). This is what my research and relationships in Khayelitsha have done for me. They have pushed me to question how I think and what I deem as important, to think more deeply and creatively, and to consider and reconsider what I have always been taught. They have made me wander the world and my daily life as an infant adult with eyes wide seeing and reflecting on things that before went unnoticed. They have forced me to recognize the messiness of the world and how it so rarely fits into neatly-made categories and labels. How I came of age in Khayelitsha is largely in learning how to think.

References

1. Cook, G. (1986). Khayelitsha: Policy Change or Crisis Response?. Transactions Of The Institute Of British Geographers. 1986;11(1):57. doi: 10.2307/622070

2. StatsSA, City of Cape Town Census Data. 2011.

3. Farmer P, Nizeye B, Stulac S, Keshavjee S. Structural Violence and Clinical Medicine. Plos Medicine. 2006;3(10): e449. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030449

4. Cooper D, De Lannoy A, Rule C. (2015). Youth health and well-being: Why it matters. South African Child Gauge, 2015:60-68. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11910/1739

5. Battersby J. Urban food insecurity in Cape Town, South Africa: An alternative approach to food access. Development Southern Africa. 2011;28(4):545-561. doi: 10.1080/0376835x.2011.605572

6. Cooper D, Harries J, Moodley J, Constant D, Hodes R, Mathews C. et al. (2016). Coming of age? Women’s sexual and reproductive health after twentyone years of democracy in South Africa. Reproductive Health Matters. 2016;24(48):79-89. doi: 10.1016/j.rhm.2016.11.010

7. Wallace D F, Kenyon College. This is water: Some thoughts, delivered on a significant occasion about living a compassionate life. New York: Little, Brown. 2009.

Author Biography