Movement for Change and Social Justice (MCSJ): A Community-University Partnership

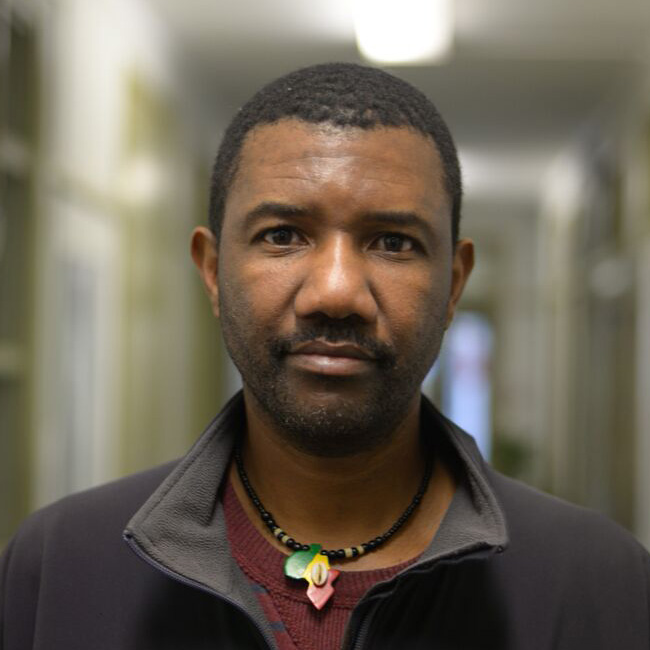

Zara Trafford (Research Fellow, UCT) and Mandla Majola (Community Engagement Coordinator, UCT)

Editorial Note: The Movement for Change and Social Justice (MCSJ) described in this interview grew out of a partnership between the Division and local NGOs and health activists in Gugulethu, Cape Town. MCSJ hopes to encourage active citizenship and to unite local organisations and individuals concerned with the wellbeing of Gugulethu residents. It has grown to become one of the Division’s main platforms for research, teaching, community engagement and health activism. Mandla Majola, the subject of this interview, is a DSBS staff member, lifelong activist and member of the Gugulethu community, and founding member of MCSJ.

The Movement for Change and Social Justice (MCSJ) is a social movement founded in Gugulethu in September 2016. MCSJ has strong links with the Division of Social and Behavioural Sciences (DSBS) at the University of Cape Town’s School of Public Health and Family Medicine. Mandla Majola (Chairperson and co-founder), a lifelong community activist and organiser, began working with DSBS in mid-2016 on a research project called iALARM, short for “Using Information to Align Services and Link and Retain Men in the HIV Cascade”. iALARM seeks to “raise the alarm” about the challenges men face in accessing HIV prevention, treatment and care. The project gathers health information about HIV prevention, treatment and care and brings this information every month to the iALARM Task Team, a multisectoral group of representatives from local government and health services, community leaders, non-governmental organisations, and research institutions.

MCSJ emerged in parallel with the work of iALARM but its objectives have grown beyond iALARM’s focus on men and HIV. Mandla has been central to the growth of both projects. Zara and Mandla sat down to discuss MCSJ’s formation and aims. Mandla spoke about the movement’s motivations, campaigns, and the benefits and challenges involved in working closely with a research institution.

The formation of MCSJ and its first campaigns

MCSJ is a social movement made up a coalition of organisations and individuals based in Gugulethu. Gugulethu is a large periurban settlement in Cape Town that is home to almost 100,000 people, many of whom live in poverty. Like other so-called “townships” in Cape Town, service delivery is inconsistent or insufficient, and rates of violence, HIV, and unemployment are extremely high. According to Mandla, MCSJ aims to “empower the community and ensure people have enough knowledge about health and social issues”. Founding organisations include the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC), Sonke Gender Justice, the Parent Centre, Grassroot Soccer, Gugulethu Sports Development Organisation (GUSDO), Soup, the local Neighbourhood Watch, and the Division of Social and Behavioural Sciences. These organisations felt that there was a large information gap in Gugulethu and a lack of collective action for social change, despite the many difficulties residents experience.

Another MCSJ campaign is against gender-based violence (GBV) because “women who were part of our meetings felt very strongly that the issue of GBV is not taken seriously, and there are no plans from government to address it”. Numerous public events and training sessions have already been held and MCSJ has focused on working with men in particular. MCSJ hopes these training sessions will be the first step in “men taking the lead in the fight against GBV”. As Mandla explained,

We have many men who have become part of the movement who see that they’ve got a role and responsibility to play… we want men to be at the forefront of confronting those individuals that are abusing, that are killing and raping women and children. We want to take it step by step – work with one man, two men, three men, try to change them… Help them to see that South Africa is transforming and they must be part of that change… Help them to create a space that is safer for boys and for girls.

The movement has borrowed from effective methods for community-based organising used by other movements and NGOs in their attempts to work with government to improve services. There is an awareness that although movements may focus on maintaining pressure on government to deliver, it is sometimes also necessary to collaborate with authorities to develop more acceptable, sustainable and equitable solutions. Groups like the TAC have successfully struck this balance between pressuring government from the outside and working with it from the inside, and MCSJ continues this tradition.

MCSJ is also rooted in a unique partnership and close working relationship with the Division of Social and Behavioural Sciences (DSBS) at UCT’s School of Public Health and Family Medicine. This offers obvious opportunities for important in-field practical learning for postgraduate students and works toward achievement of the university’s commitment to social engagement. More importantly, from MCSJ’s perspective, this direct link to research institution is valuable in a variety of ways. The university is relatively well-resourced, has access to valuable health information as well as institutional power not otherwise available to most social movements, and is able to mobilise its networks for widespread communication and impact.

Initially formed around a series of short-term campaigns, MCSJ has grown into a formal social movement. Looking to the future, MCSJ aims to create “a space where people can come together for a good cause and we give each other solidarity, support one another, care about one another, address these issues, and create a space for people from different walks of life to partake and to contribute and to make a change”. As Mandla explained, “people from Gugs felt very strongly that, ‘this is not your [MCSJ’s] project – this is our project. We want this to continue. We want to showcase what we can achieve working as the community, a research institution and government, in this area’”. Through their campaigns and a responsive approach to emerging issues, MCSJ aims to drive active citizenship, to support multisectoral collaboration, and to keep strategic pressure on local authorities for the improved delivery of services.

A community event to disseminate research findings

When asked about the value of working closely with research institutions, Mandla first noted the importance of working with an institution like UCT because it has “got tons and tons of information and if that goes back to the community, it can make a difference”. In fact, the lack of access to information in Gugulethu was a key motivation for building a strong social movement in the area. Mandla had seen first-hand how valuable and impactful access to proper information was in the fight against HIV in Khayelitsha. As a result, “the majority of people are now more open about their status, partly because of years of sustained and strategic activism” by health and other activist organisations in the area. In contrast, talking with iALARM interview participants, Mandla had been “shocked” at the high rates of stigma and discrimination still experienced by people living with HIV in Gugulethu.

To begin the journey to more democratised access to information, DSBS and MCSJ held a community meeting to share findings from iALARM, an ongoing DSBS research project being conducted in Gugulethu. On 11 July 2018, Chris Colvin (HoD) presented findings from this project, including the high rates of stigma and discrimination felt by men with HIV in Gugulethu, the social, economic and health systems factors that made it difficult for them to access HIV prevention and care, and the experiences and insights of men who were resilient and remained successfully in care despite these challenges. The Deputy Director of the Department of Health’s Directorate of HIV/AIDS, STIs and TB was the second speaker, having approached MCSJ and asked to be involved with the event. MCSJ mobilised people to attend the event with a target of approximately 500 attendees. On the day, almost 1,400 people from all over Gugulethu arrived. Mandla explains further,

We never expected to receive such huge support from Gugulethu and the surrounding communities. People really expressed themselves about their health conditions. We had men talking about the health challenges they are experiencing, and the help that they need. We also advertised the services being offered at the Sonke Gender Justice Men’s Clinic. People appreciated that a research institution had come and done research in their community but also had the decency and the respect to come back and give a report, be held accountable, and get the views of the community. It acknowledges that the story, the data, is an outcome of two groups – the community and the research institution, and that was really beautiful.

Mandla explained that the movement plans “to find ways of ensuring the community opens up to these things to help them… identify the problems but also, to be part of the change that they want in their own community.” MCSJ wants to help people “welcome this information with open arms, ensure that we grasp it, make sense of it, and try to implement things that can change the community”.

Social movements and universities

Mandla felt that universities have a specific responsibility to “recognise communities as equal partners in the co-creation of knowledge”. A starting point would be not only to inform people that research is being done in the area but importantly, to communicate the findings of this research in a shared forum. He believes the 11 July event provides “a model that could expand to other departments in the School of Public Health and Family Medicine who are doing similar work in Gugulethu”. Such events would offer a platform for sharing research reports in a space allowing for proper engagement with the community in question. Mandla felt that this would be powerful and would,

help the community make people aware of what is going on in their own community, and also help them to be part of mechanisms or ways of changing how they think, how they perceive HIV (if it’s about HIV), and what needs to be done – as the Department of Health, as the community, and as individuals. That dialogue is very important between communities, research institutions, government, and activists, under the same roof.

Beyond the benefits of bringing research results and other kinds of health information to the community, Mandla sees other longer-term benefits to this kind of community-university partnership. For example, although UCT has done extensive research in the area and there are many young people living there who would benefit from access to tertiary education, Mandla expressed concern because “the number of people studying at UCT who are from Gugulethu is not enough”. He hopes to establish a close relationship between UCT researchers and community members, to inspire them to study at a university and bring their knowledge and expertise back to the community, and suggested one way to begin,

We need to take responsibility for bringing UCT’s orientation or open day events to Gugulethu so that young people can benefit and find a way of bridging the gap, ensuring they’re able to access tertiary education, and feel inspired. If there are young people from Gugulethu at UCT, we could bring them to talk there so that they can see that that person comes from their area and has graduated, has a Masters or a PhD. Because what they see every day…these are not good sights. Drug lords who are driving flashy cars. So they don’t see people who have earned their success through hard work because those people end up moving out of Gugs to stay in more affluent areas because they become easy targets. So, this partnership between MCSJ and UCT can grow from strength to strength if we put our minds to it.

While he hopes that people don’t “think MCSJ is a solution to everything, a magic bullet”, Mandla feels positive that with small, incremental steps the movement can make a significant change in Gugulethu.

Author Biographies

Email: zara.trafford@uct.ac.za