Penile-Vaginal Heteronormativity in Defining Sex, Virginity, and Abstinence: Implications for Research and Public Health in sub-Saharan Africa

Zoe Duby

Editorial note: Zoe Duby is a qualitative researcher in the field of sexuality and HIV prevention. In this piece, she reflects on how the ambiguity and lack of precision of sex-related definitions affect 1) the accuracy of data in research and clinical practice; 2) sexual decision making and risk behaviour; and 3) the accuracy of data on penile-anal intercourse. These issues are framed within the context of HIV research and programming, but their relevance extends to any sex-related field.

Introduction

The manner in which sexual behaviour terms are defined, operationalised and interpreted has implications for research, policy, and clinical practice, and is central to ensuring the accuracy of reporting and the efficacy of interventions. Understanding how people conceptualise and define sex-related terms is vital for meaningful research and health interventions, especially for epidemics that are predominantly transmitted through sex, such as HIV in Africa. Nonetheless, much of the terminology relating to sex acts remains inconsistent and imprecise. A deeper exploration of these ambiguous terms – regularly used in research and clinical practice – and how they are understood sheds light on how phallo-vagino-centric heteronormative assumptions have shaped the study of sexual behaviour and the provision of sexual health interventions in the sub-Saharan African region.

The language we use to describe sex shapes our understanding of sex and mediates our sexual experiences. Sociocultural codes and conventions enable us to identify specific experiences and acts as sexual or not (1). Despite being widely used in research, clinical practice and everyday speech though, there exists no uniform, universally-accepted, context-independent definition of the word ‘sex’ and related terms. However, the HIV epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa is commonly understood to be primarily ‘sexually-transmitted’ and is considered the largest HIV epidemic driven by ‘heterosexual sex’ in the world (2). Most generalised HIV prevention efforts in the region have focused on ‘heterosexual sex’ as the key transmission vector, with transmission to women assumed to occur through ‘heterosexual sex’.

The HIV epidemic is therefore an important opportunity to examine scientific understanding of and language pertaining to ‘sex’. Research on how these concepts have been defined and conceptualised in African settings is scarce, and has largely focused on abstinence (3,4), or language and metaphors around sex (5,6). In efforts to find ‘African solutions’ to ‘the African AIDS problem’, programmes focusing on delaying sexual debut and promoting abstinence have formed a large part of HIV prevention efforts in Africa. Little attention, however, has been paid to how these concepts of sexual debut and abstinence have been defined, understood, and operationalised.

Ambiguous definitions affect the accuracy and quality of our data, as well as how HIV prevention messaging is interpreted by the public (7). There is a growing recognition of these problems of definitions in the United States and Europe, and increasing efforts to use terminology that is clearer and less ambiguous. However, despite Africa’s sexually transmitted HIV epidemic, this recognition and shift seems not to have taken place yet in most sex research on the continent. In this piece, the concepts of sex, virginity and abstinence are examined, highlighting how these and terms have been defined and operationalised in socio-behavioural research on sex and in HIV interventions in sub-Saharan Africa, as well as how they have been understood by research participants. These reflections are drawn from over a decade (beginning in 2006) of qualitative research exploring heterosexual penile-anal intercourse in the context of five sub-Saharan African countries.

Definitions of Sex

Pervasive and widely used terms (such as ‘sex’, ‘intercourse’ and ‘coitus’) refer to sexual behaviour but generally remain ambiguous and lack clear, explicit definition. A number of terms relating to an individual’s ‘commencement of sexual activity’—such as ‘sexual debut’—are also unclear. These terms are commonly used in research and clinical practice in sub-Saharan Africa, but they rely on a phallo/vagino-centric heteronormative assumption. The terms phallo/vagino-centric or penile-vaginal penetrative heteronormativity refer to the ‘coital imperative’, an assumption that the ultimate objective of sex is penetrating the vagina with the penis, an assumption privileged above all else (8-10). It is typically assumed that discussions around ‘sex’ or related acts will be in reference to penetrative, penile-vaginal intercourse between a man and a woman (11,12). Similarly, heteronormativity means that heterosexuality is understood within the dominant social norms as the natural and normal sexual orientation (13,14).

People’s own definitions of sex are fluid and dependent on intention, context and factors at individual, interpersonal, and socio-cultural levels. Individual factors include gender, age, religiosity, ethnicity, HIV serostatus, sexual orientation, past sexual experience, and sexual socialisation (parents’/community’s permissiveness) (17). Motivations for defining sex also play a part; the same physical act may be defined in different ways by an individual depending on the anticipated consequences of the definition (18). Interpersonal factors include gender of sexual partners involved, the relationship context in which sex occurs, whether the act was consensual or not, and occurrence of orgasm, amongst others. At the socio-cultural level, influential factors include gendered sexual norms, religious beliefs around the importance of virginity, and the link between sex and reproduction. Sexual behaviour is thus “socially constructed” – different behaviours are defined as sexual and imbued with certain meanings across different cultural and social contexts. Definitions of sex are also influenced by factors relating to the audience—clinician/researcher/sexual partner—whose own interpretations will be influenced by their assumptions and many of the above mentioned factors. Despite the influence of these factors, individuals have some degree of agency in negotiating their own experience and definitions of sex. The complex interplay of the factors described here contributes to the ambiguous, sometimes contradictory definitions and conceptualisations of sex-related terms (19,20).

Definitions of Virginity

Most classifications of virginity loss, sexual debut and being sexually active in research from sub-Saharan Africa have been based on heterosexual penile-vaginal intercourse (21-23). However, this assumption is rarely explicitly cited, and despite a voluminous literature on virginity testing in South Africa (where the bulk of this data comes from), there is little mention of how ‘virginity’ and ‘sex’ are defined. Nonetheless, the penetration of a woman’s vagina by a penis is commonly perceived to be the act that enables her to transition to sexual maturity and womanhood (13,24). Female anatomical virginity is central to normative ideas of virginity in Africa, with ‘hymenal virginity’ (the integrity of the hymen, the porous membrane covering the lower end of the vagina) being the most common marker, despite the fact that this is an unreliable indicator of whether a vagina has been penetrated by a penis (14,24-29). This lack of clarity can have serious implications. For young Zulu women, for example, failing a virginity test may result in social exclusion, shame, and jeopardised marriage prospects. With the concept of female virginity in Africa and elsewhere so closely aligned with the vagina, this raises the question of how male virginity should be defined (26,28,29). There is still ambiguity about how sexual activities other than penile-vaginal sex are situated in conceptualisations of virginity and virginity loss.

There is an implicit assumption that rather than being fluid and contextually specific, definitions of sex-related terms are robust and universal

There are value associations attached to being a virgin or non-virgin, which affect how the terms themselves are defined. People often choose to disregard or modify the dominant definition of virginity loss to suit their own purposes (14). The social desirability of virginity also has a gendered dimension. Virginity can be stigmatising for male adolescents, whereas the loss of virginity can be stigmatising for female adolescents. Male adolescents, more eager to transition to a non-virgin status, are more likely to consider a greater variety of sexual behaviours as constituting virginity loss than females (30). In contrast, individuals who consider virginity at marriage important are less likely to include behaviours like oral sex and anal sex in their definitions of sex or virginity loss, in order to maintain their virgin status and a positive social identity (30).

There are also implications for sexual health and risk reduction. Social pressure to remain a virgin is likely to increase the risk of infection by acting as a barrier to young people’s use of prevention and encouraging alternative, non-vaginal sexual practices. With the idea that neither oral sex nor penile-anal intercourse constitute sex or a loss of virginity, non penile-vaginal sexual acts are used as a means of maintaining ‘technical’ virginity, practicing abstinence and delaying sexual debut, despite the fact that practices such as anal sex may actually significantly increase risk of HIV infection (34-40). Examples of this can be found amongst young Zulu women in South Africa, who engage in penile-anal sex in order to maintain the integrity of their hymens and thus pass ‘virginity tests’ (41-44).

Definitions of Abstinence

Similar to assumptions that having sex equates with a penis entering a vagina, the term ‘abstinence’ is most commonly based on the non-occurrence of heterosexual penile-vaginal sex (36,37). Historically, intervention designers and policymakers targeting ‘sexual debut’ and ‘abstinence’ have neglected to specify what the terms actually mean (45,46). Definitions of abstinence used by institutions such as UNAIDS, USAID and PEPFAR include terms such as ‘not engaging in sexual intercourse’, ‘delaying sexual initiation’ and ‘postponing sex’, but fail to explicitly define these terms (4,14,18,37). Abstinence proponents, often connected to faith-based institutions, generally define abstinence in moral terms, using ambiguous language such as ‘chaste’ or ‘virgin’ and framing abstinence as a ‘commitment to chastity’ (45).

Researchers also need to be cognisant of the fluidity and inconsistency of sexual behaviour terminology, and increased attention needs to be paid to the variables and contextual factors that influence the ways in which sexual behaviour is defined and classified, particularly when it has implications for HIV and STI risk

Like sex and virginity however, individuals define what they mean by abstinence depending on context and situation. Evidence suggests that abstinence definitions are even more fluid than virginity; for example, the definition of whether or not someone is abstinent often being based on the period of time that has elapsed since they last engaged in ‘sex’ (47). Further, the way in which abstinence is defined differs throughout stages of adolescence and adulthood (48). Research examining how young people in sub-Saharan Africa define the concept of abstinence has found that definitions are variable and interpretations of ‘abstinence’ include ‘stopping sex’, not wanting to have sex, not having sex specifically in order to avoid contracting HIV, and refraining from premarital sex (4,49).

The use of imprecise, ambiguous terminology in research and clinical practice

The reliability of data and the use of ambiguous and undefined terms such as sexual intercourse, sex and virginity has implications for HIV interventions. Historically, many HIV prevention programmes in Africa aimed at young people have focused on advocating delayed sexual debut, abstinence, and virginity maintenance, often without clearly defining these concepts and behaviours (55). These ambiguous concepts have also been used as indicators for the effective monitoring of national HIV programs, and in sub-Saharan African National Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), intended to collect and disseminate accurate and nationally representative data on public health. There is an implicit assumption that rather than being fluid and contextually specific, definitions of sex-related terms are robust and universal. Adolescents who have not had sex or ‘debuted sexually’ may have already engaged in penile-anal sex and oral sex, but this information is typically not captured in research or clinical history taking (23). While penile-anal sex may be practiced as a means of maintaining virginity, delaying sexual debut, and remaining abstinent, reasons for adopting these behaviours also include a perceived lower risk of adverse health or social consequences due to misinformation (51,55,56). In reality, these terms are deeply subjective and socio-culturally defined, and their interpretation and meaning varies widely.

Recommendations

Hunt and Davies (1991) suggested that there are three approaches to dealing with the challenge of sex definitions in sex research. The first is to ignore the question of how sex is defined, assuming that the imprecision of language is trivial and will be swept up in the sampling process, and that differences in meaning between participants/researchers will be minor and insignificant. The second approach is the imposition of terms with strictly defined meanings that result from pilot testing of terms, thus providing a common currency for discussion. The third approach is an in-depth investigation of the various terms used by the target study population, and then the employment of these terms as the basis of subsequent investigation. Below I offer two additional recommendations.

Researchers and those working in clinical practice should use behaviourally specific, unambiguous language in order to ascertain accurate information about sexual behaviour and sexual risk from participants/patients, not assuming a mutually shared definition of terms (40,54,57,58). In order to ensure effective education and risk prevention, words that have any potential for ambiguity or multiple interpretations should be avoided (57). Researchers also need to be cognisant of the fluidity and inconsistency of sexual behaviour terminology, and increased attention needs to be paid to the variables and contextual factors that influence the ways in which sexual behaviour is defined and classified, particularly when it has implications for HIV and STI risk.

Conventional language related to sex fails to encompass the varied sexual practices that humans engage in, provide for the different boundaries that people draw around what constitutes sex and what does not, and fails to reflect the fluidity and contextuality of notions of virginity, abstinence, and definitions of sexual acts

The focus of this piece has been on the English-language terminology around sex, virginity and abstinence as this is the dominant language of medical research and clinical practice, both in sub-Saharan Africa and more broadly in global health. The definitional and conceptual dilemmas around sex-related terms are amplified in cross-cultural research, where it should be ensured that translated terms are equivalent, accurate, precise, unambiguous and inoffensive (53). In multi-lingual contexts, attention to ambiguity is particularly important and complex, especially where terms may have multiple possible interpretations or translations (53). In order to improve risk assessments, and for the clear, unambiguous standardised communication of information, the challenge lies in developing operational terms that are as physiologically precise as language allows and are sexuality- and value-neutral.

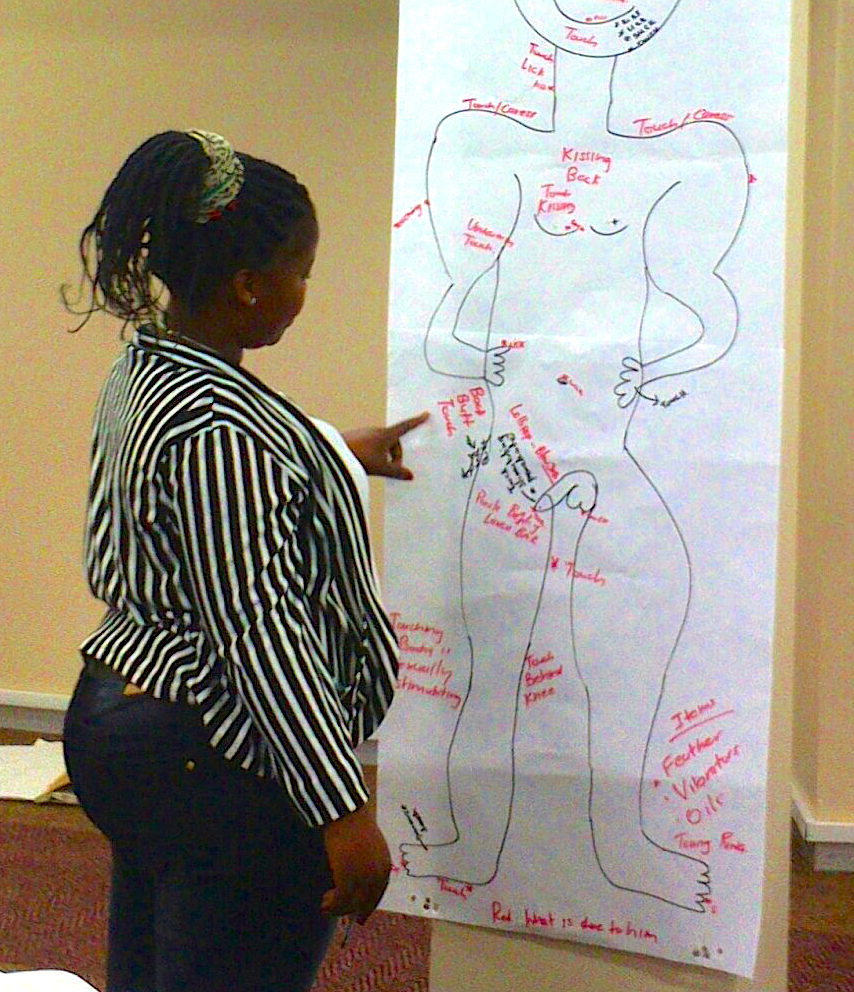

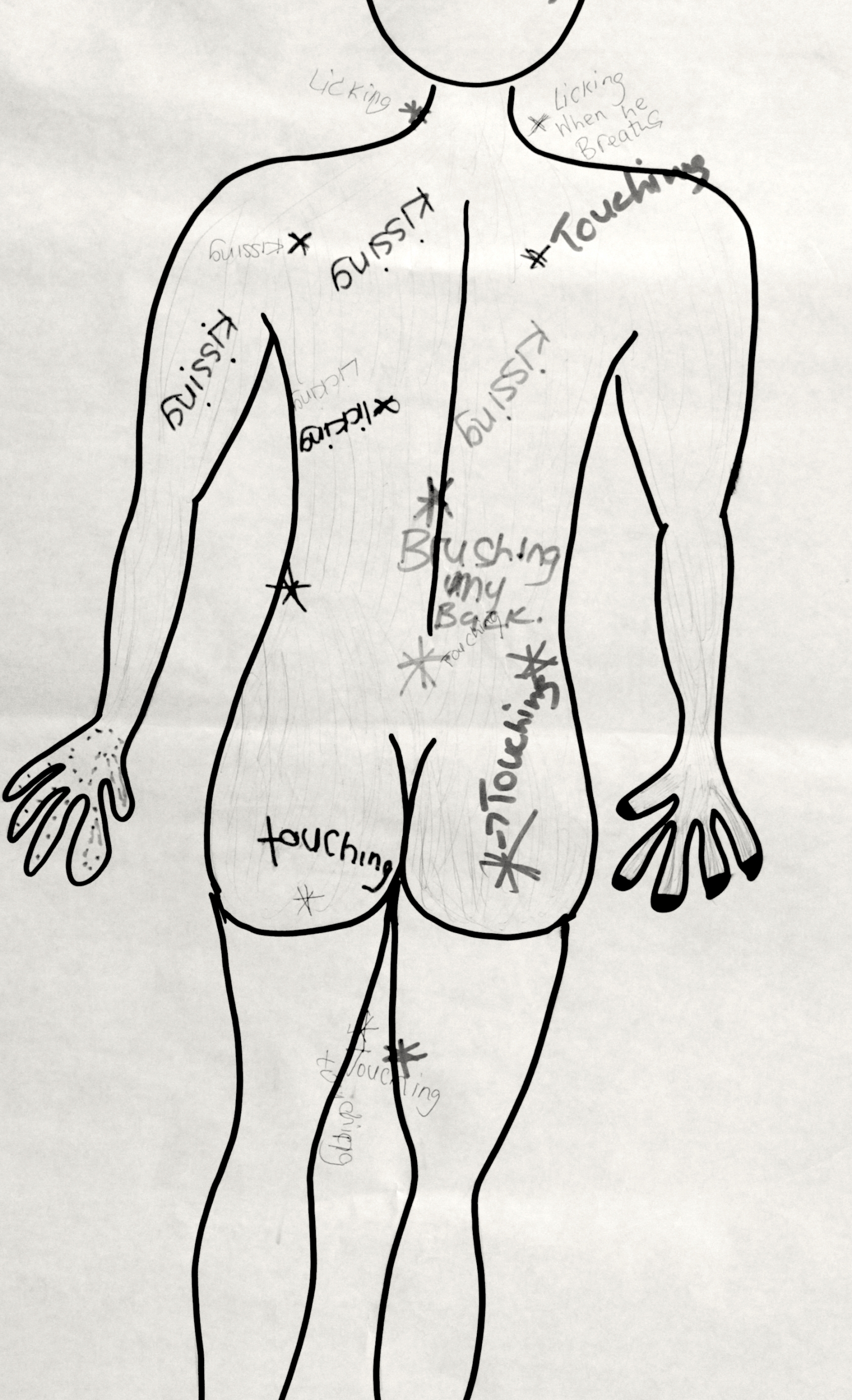

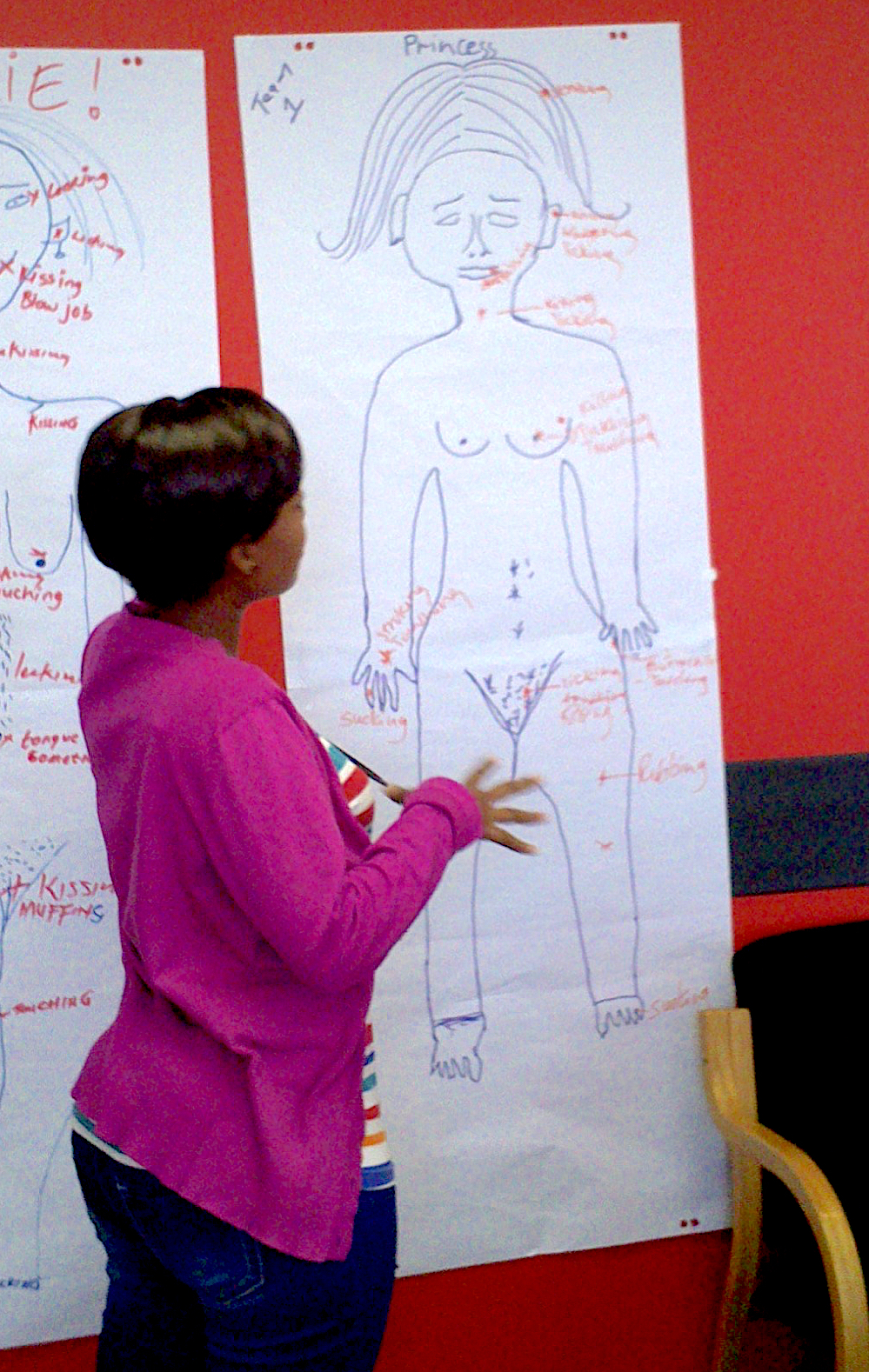

It may not be possible to resolve the substantial terminological challenges shared by researchers, prevention specialists and clinicians simply by proposing the adoption of biologically- and behaviourally-specific definitions. The latter has been tried many times and found to have both strengths and weaknesses, and additional challenges arise when explicit definitions make patients/participants and researchers uncomfortable. It is important to appreciate that these recommendations are themselves culture-bound and limiting, and may be seen to negate cultural and linguistic diversity (53). However, the clear impact of terminological challenges on research and practice provide an impetus for working toward improving our shared understanding. Further exploration into how innovative research methods, such as visual tools, body mapping exercises and three-dimensional models, could be used to reduce misinterpretation and ambiguity of terms (53).

Conclusions

Like sex research more broadly, the bulk of research on virginity, sexual debut and abstinence in Africa, has also been based on heteronormative, vagino-centric assumptions. Conventional language related to sex fails to encompass the varied sexual practices that humans engage in, provide for the different boundaries that people draw around what constitutes sex and what does not, and fails to reflect the fluidity and contextuality of notions of virginity, abstinence, and definitions of sexual acts. Other sexual behaviours have been largely overlooked and excluded from research and clinical practice as a result of the assumptions embedded in commonly used terms and definitions, as well as due to denial, taboo and sexual communication norms.

Greater attention needs to be paid to the complexity, problematic ambiguity and inconsistency of conceptualisations and definitions of sex-related terms. Although sex, virginity and abstinence are social and contextual constructs whose meaning and interpretation varies across individuals, these terms continue to be used as if their meanings were unambiguous. As shown here, this can affect the quality and accuracy of data, with considerable implications for HIV and other sexual health interventions.

References

1. Diorio JA. Changing Discourse, Learning Sex, and Non-coital Heterosexuality. Sexuality & Culture. Springer US; 2016 May 13;20(4):841–61.

2. Owen BN, Elmes J, Silhol R, Dang Q, McGowan I, Shacklett B, et al. How common and frequent is heterosexual anal intercourse among South Africans? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the International AIDS Society. Taylor & Francis; 2017 Jan 11;20(00):1–14.

3. Izugbara CO. Masculinity Scripts and Abstinence-Related Beliefs of Rural Nigerian Male Youth. 2008 Aug 6;:1–16.

4. Winskell K, Beres LK, Hill E, Mbakwem BC, Obyerodhyambo O. Making sense of abstinence: social representations in young Africans' HIV-related narratives from six countries. Culture, Health & Sexuality [Internet]. 2011 Jul 29;13(8):945–59. Available from: http://web.a.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.uct.ac.za/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=70ba50b8-7ef8-4bf3-9f31-057f6140cdc6%40sessionmgr4002&vid=2&hid=4204.

5. Cain D, Schensul S, Mlobeli R. Language choice and sexual communication among Xhosa speakers in Cape Town, South Africa: implications for HIV prevention message development. Health Education Research. 2011 May 22;26(3):476–88.

6. Undie C-C, Crichton J, Zulu E. Metaphors We Love By: Conceptualizations of Sex among Young People in Malawi. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2007 Dec 4;11(3):221–35.

7. Shayo EH, Kalinga AA, Senkoro KP, Msovela J, Mgina EJ, Shija AE, et al. Prevalence and risk factors associated with female anal sex in the context of HIV/AIDS in the selected districts of Tanzania. BMC Research Notes. BioMed Central; 2017 Mar 25;:1–10.

8. Hyde A. The politics of heterosexuality—a missing discourse in cancer nursing literature on sexuality: A discussion paper. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2007 Feb;44(2):315–25.

9. McPhillips K, Braun V, Gavey N. The ambiguity of “having sex”: The subjective experience of virginity loss in the United States. Journal of Sex Research [Internet]. Taylor & Francis; 2001;38(2):127–39. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277539501001601.

10. Murphy M. Hiding in Plain Sight: The Production of Heteronormativity in Medical Education. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography. 2016 May 6;45(3):256–89.

11. Pham JM. The Limits of Heteronormative Sexual Scripting: College Student Development of Individual Sexual Scripts and Descriptions of Lesbian Sexual Behavior. Frontiers in Sociology. 2016 Jun 14;1(7):1–10.

12. Rupp LJ. Sexual Fluidity “Before Sex.” Signs. 2012 Jun 9;37(4):849–56.

13. Cornwall S. Ratum et Consummatum: Refiguring Non-Penetrative Sexual Activity Theologically, in Light of Intersex Conditions. Theology Sexuality. 2010 Feb 4;16(1):77–93.

14. Medley-Rath SR. “Am I Still a Virgin?”: What Counts as Sex in 20 years of Seventeen. Sexuality & Culture [Internet]. 2007 Aug 31;11(2):24–38. Available from: http://www.springer.com/social+sciences/journal/12119?hideChart=1.

15. Huang H. Cherry Picking: Virginity Loss Definitions Among Gay and Straight Cisgender Men. Journal of Homosexuality. Routledge; 2017 Aug 19;00(00):1–14.

16. Bond J. Gender and Non-Normative Sex in Sub-Saharan Africa. Michigan Journal of Gender and Law. 2016 Oct 31;23(1):65–145.

17. Randall HE, Byers ES. What is sex? Students' Definitions of Having Sex, Sexual Partner, and Unfaithful Sexual Behaviour. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality. 2003;12(2):1–11.

18. Peterson ZD, Muehlenhard CL. What Is Sex and Why Does It Matter? A Motivational Approach to Exploring Individuals' Definitions of Sex. Journal of Sex Research [Internet]. 2007 Sep 9;44(3):256–68. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00224490701443932

19. Carpenter LM. Gender and the meaning and experience of virginity loss in the contemporary United States. Gender & Society. Sage Publications; 2002;16(3):345–65.

20. Faulkner SL. Good Girl or Flirt Girl: Latinas' Definitions of Sex and Sexual Relationships. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2003 May 1;25(2):174–200.

21. Gute G, Eshbaugh EM, Wiersma J. Sex for You, But Not for Me: Discontinuity in Undergraduate Emerging Adults' Definitions of ‘Having Sex’. Journal of Sex Research. 2008 Nov 3;45(4):329–37.

22. Humphreys TP. Cognitive Frameworks of Virginity and First Intercourse. Journal of Sex Research [Internet]. 2013 Aug 12;50(7):664–75. Available from: http://web.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.uct.ac.za/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=45fad503-917c-411f-8811-48963f04df13%40sessionmgr198&vid=2&hid=125

23. Schuster MA, Bell RM, Kanouse DE. The sexual practices of adolescent virgins: genital sexual activities of high school students who have never had vaginal intercourse. Am J Public Health. American Public Health Association; 1996;86(11):1570–6.

24. Ergun E. Reconfiguring Translation as Intellectual Activism: The Turkish Feminist Remaking of Virgin: The Untouched History. Trans-Scripts. 2013 May 1;3:264–89.

25. Addison C. Enlightenment and virginity. Inkanyiso: Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences [Internet]. Forum Press; 2011 Jan 20;2(2):71–7. Available from: http://www.ajol.info/index.php/ijhss/article/view/63478/51322

26. Behrens KG. Virginity testing in South Africa: a cultural concession taken too far? South African Journal of Philosophy. 2014 Jul 7;33(2):177–87.

27. Leclerc Madlala S. Virginity testing: Managing sexuality in a maturing HIV/AIDS epidemic. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. Wiley Online Library; 2001;15(4):533–52.

28. Polanco EA. “The Chamber of Your Virginity does not have a Price”: The Scientific Construction of the Hymen as an Indicator of Sexual Initiation in Eighteenth-Century Spain. Footnotes A Journal of History. 2017 May 2;1:67–88.

29. Wickstrom A. Virginity testing as a local public health initiative: a ‘preventive ritual’ more than a ‘diagnostic measure’. 2010 Aug 6;:1–20.

30. Wright MR. Defining Sex and Virginity Loss. MA Thesis, Ball State University. 2011 Jul 28;:1–60.

31. Berger DG, Wenger MG. The Ideology of Virginity. Journal of Marriage and the Family; 1973.

32. Brückner H, Bearman P. After the promise: the STD consequences of adolescent virginity pledges. Journal of Adolescent Health 36 (2005) 271–278. 2005 Mar 10;:1–8.

33. Carpenter LM. Like a Virgin…Again?: Secondary Virginity as an Ongoing Gendered Social Construction. Sexuality & Culture. 2010 Dec 16;15(2):115–40.

34. Blake C. The value Sexual Health Education in South Africa: A retrospective evaluation by recent matriculants. University of the Witwatersrand. 2016 Sep 7;:1–118.

35. Carpenter LM. The Ambiguity of “Having Sex”: The Subjective Experience of Virginity Loss in the United States. The Journal of Sex Research. 2001 May 8;38(2):1–13.

36. Cherie A, Berhane Y. Oral and anal sex practices among high school youth in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):5.

37. Haglund K. Sexually abstinent African American adolescent females' descriptions of abstinence. Journal of Nursing Scholarship [Internet]. Wiley Online Library; 2003 Sep 25;35(3):231–6. Available from: http://web.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.uct.ac.za/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=d6cf20fe-5c42-43b7-80d5-0e03529e0e4f%40sessionmgr111&vid=2&hid=108

38. Pitts M, Rahman Q. Which behaviors constitute “having sex” among university students in the UK? Arch Sex Behav. Springer; 2001;30(2):169–76.

39. Rostosky SS, Regnerus MD, Wright MLC. Coital debut: The role of religiosity and sex attitudes in the Add Health Survey. Journal of Sex Research. Taylor & Francis; 2003;40(4):358–67.

40. Sanders SA, Reinisch JM. Would you say you had sex if...? Jama. American Medical Association; 1999;281(3):275–7.

41. Day E, Maleche A. Traditional Cultural Practices & HIV: Reconciling Culture and Human Rights. Global Commission on HIV and the Law. 2011 Jul 24;:1–21.

42. Kunene ZZ. Exploring experiences of virginity testers in Mtubatuba area, KwaZulu-Natal. 2015 May 18;:1–104.

43. Leclerc Madlala S. On the virgin cleansing myth: gendered bodies, AIDS and ethnomedicine. African Journal of AIDS Research. 2002 Jan;1(2):87–95.

44. Roux LL. Hamful Traditional Practices, (Male Circumcision and Virginity Testing of Girls) and the Legal Rights of Children. 2006 Nov 3;:1–85.

45. Santelli JS, Kantor LM, Grilo SA, Speizer IS, Lindberg LD, Heitel J, et al. Abstinence-Only-Until-Marriage: An Updated Review of U.S. Policies and Programs and Their Impact. JAH. Elsevier Inc; 2017 Sep 1;61(3):273–80.

46. Underhill K, Montgomery P, Operario D. Abstinence-plus programs for HIV infection prevention in high-income countries (Review). Evidence-Based Child Health a Cochrane Review Journal. 2009 May 29;4:400–815.

47. Bersamin MM. Defining virginity and abstinence: Adolescents’ interpretations of sexual behaviors. 2007 Aug 8;:1–8.

48. Ott MA, Pfeiffer EJ, Fortenberry JD. Perceptions of Sexual Abstinence among High-Risk Early and Middle Adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006 Aug;39(2):192–8.

49. Mokwena K, Morabe M. Sexual abstinence: What is the understanding and views of secondary school learners in a semi-rural area of North West Province, South Africa? SAHARA-J Journal of Social Aspects of HIVAIDS. 2016 Jun 16;13(1):81–7.

50. Hill BJ, Rahman Q, Bright DA, Sanders SA. The semantics of sexual behavior and their implications for HIV/AIDS research and sexual health: US and UK gay men's definitions of having ‘had sex’. AIDS Care. Taylor & Francis; 2010;22(10):1245–51.

51. Mavhu W, Langhaug L, Manyonga B, Power R, Cowan F. What is “sex” exactly? Using cognitive interviewing to improve the validity of sexual behaviour reporting among young people in rural Zimbabwe. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2008 Aug;10(6):563–72.

52. Mehta CM, Sunner LE, Head S, Crosby R, Shrier LA. ``Sex Isn't Something You Do with Someone You Don't Care About'‘: Young Women’s Definitions of Sex. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology [Internet]. Elsevier Inc; 2011 Oct 1;24(5):266–71. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1083318811001161

53. Duby Z, Hartmann M, Mahaka I, Munaiwa O, Nabukeera J, Vilakazi N, et al. Lost in Translation: Language, Terminology, and Understanding of Penile–Anal Intercourse in an HIV Prevention Trial in South Africa, Uganda, and Zimbabwe. The Journal of Sex Research. 2015 Oct 27;:1–12.

54. Hill BJ, Sanders SA, Reinisch JM, Hill BJ, Reinisch JM. Variability in Sex Attitudes and Sexual Histories Across Age Groups of Bisexual Women and Men in the United States. Journal of Bisexuality. Taylor & Francis; 2016 Mar 3;16(1):20–40.

55. Duby Z, Colvin C. Conceptualizations of Heterosexual Anal Sex and HIV Risk in Five East African Communities. Journal of Sex Research. Taylor & Francis; 2014;(ahead-of-print):1–11.

56. Hensel DJ, Fortenberry JD, Orr DP. Variations in Coital and Noncoital Sexual Repertoire among Adolescent Women. Journal of Adolescent Health [Internet]. 2008 Jan 15;42(2):170–6. Available from: http://ac.els-cdn.com.ezproxy.uct.ac.za/S1054139X07003205/1-s2.0-S1054139X07003205-main.pdf?_tid=2b2efc9c-16df-11e3-ae27-00000aab0f01&acdnat=1378463531_bf5c8d2eacd27048758aad5cf6f9da42

57. Barnett MD, Fleck LK, Marsden AD III, Martin KJ. Sexual semantics: The meanings of sex, virginity, and abstinence for university students. PAID. Elsevier Ltd; 2017 Feb 1;106(C):203–8.

58. Menn M, Goodson P, Pruitt B, Peck-Parrott K. Terminology of Sexuality Expressions that Exclude Penetration: A Literature Review. American Journal of Sexuality Education [Internet]. 2011 Oct;6(4):343–59. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com.ezproxy.uct.ac.za/doi/pdf/10.1080/15546128.2011.625721.

Author Biography

Email: zoe.duby@gmail.com