Clinical Ethics Forum: 2025 in Review

All healthcare professionals face competing obligations to their patients, employers, and themselves, and dealing with these can lead to moral distress—uncertainty about knowing what the right thing to do is. In South Africa, this distress is compounded by a combination of declining healthcare resources, crumbling infrastructure, an increasing burden of disease, enduring healthcare inequalities, and the additional burdens of violence and substance use in our population. Numerous studies have shown the physical and mental effects of moral distress, which not only negatively affect healthcare providers but also directly and indirectly affect the efficiency and quality of healthcare delivery.

In this context, it is unlikely that we can banish this experience entirely for healthcare workers. Exploring better ways to support them is therefore critical, given the increasing evidence of a causal relationship between moral distress and burnout, job performance, patient care, and workplace attrition.

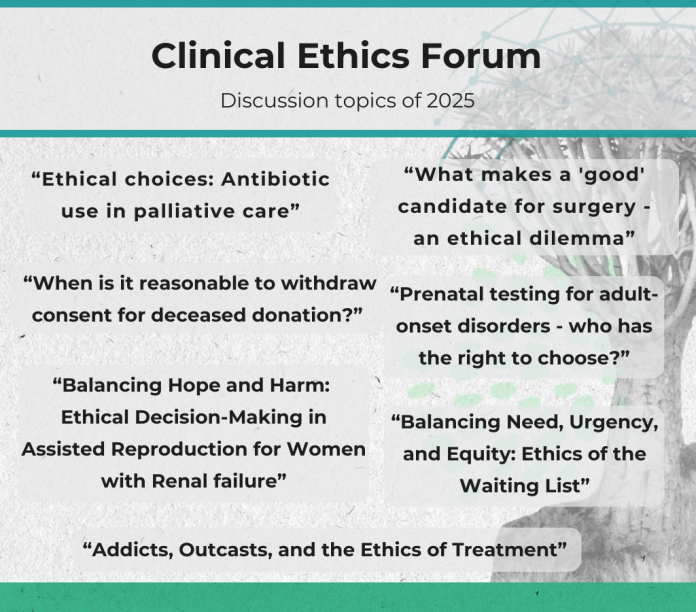

The idea that an environment aimed at encouraging moral decision-making and empowering decision-makers to act can offer a way to counter moral distress led to the establishment of a monthly Clinical Ethics Forum (CEF), hosted by EthicsLab and held at the Neuroscience Institute. The aim of these meetings is to offer clinicians the opportunity to explore the moral components of distressing clinical situations or encounters and to provide them with tools to address these. The CEFs bring together people from diverse disciplines, including moral philosophers, bioethicists, psychiatrists, palliative care clinicians, other healthcare professionals, and medical management. At each CEF, a clinician or clinical team presents a clinical case study they have found distressing, after which attendees are invited to explore the case from different practical, clinical, and ethical angles.

Cases this year raised questions about our obligations to international patients on medical visas in the face of budget cuts affecting our own population, whether pregnant women can be required to take ARVs against their will to secure the health of their unborn babies, and how to cope with patients whose religious convictions prevent them from accepting life-saving treatment. We were also exposed to the reality that injuries related to road accidents and violence, which require emergency surgery, mean that patients with treatable tumours slip further down surgery waiting lists, leading to life-altering—and even life-shortening—consequences.

Despite the depressing nature of the cases, the CEFs themselves are not depressing. Rather, they showcase how the creation of safe, supportive, and convivial spaces can promote productive ways of dealing with the ethical complexities that characterise healthcare settings.