Can generative AI shift power?

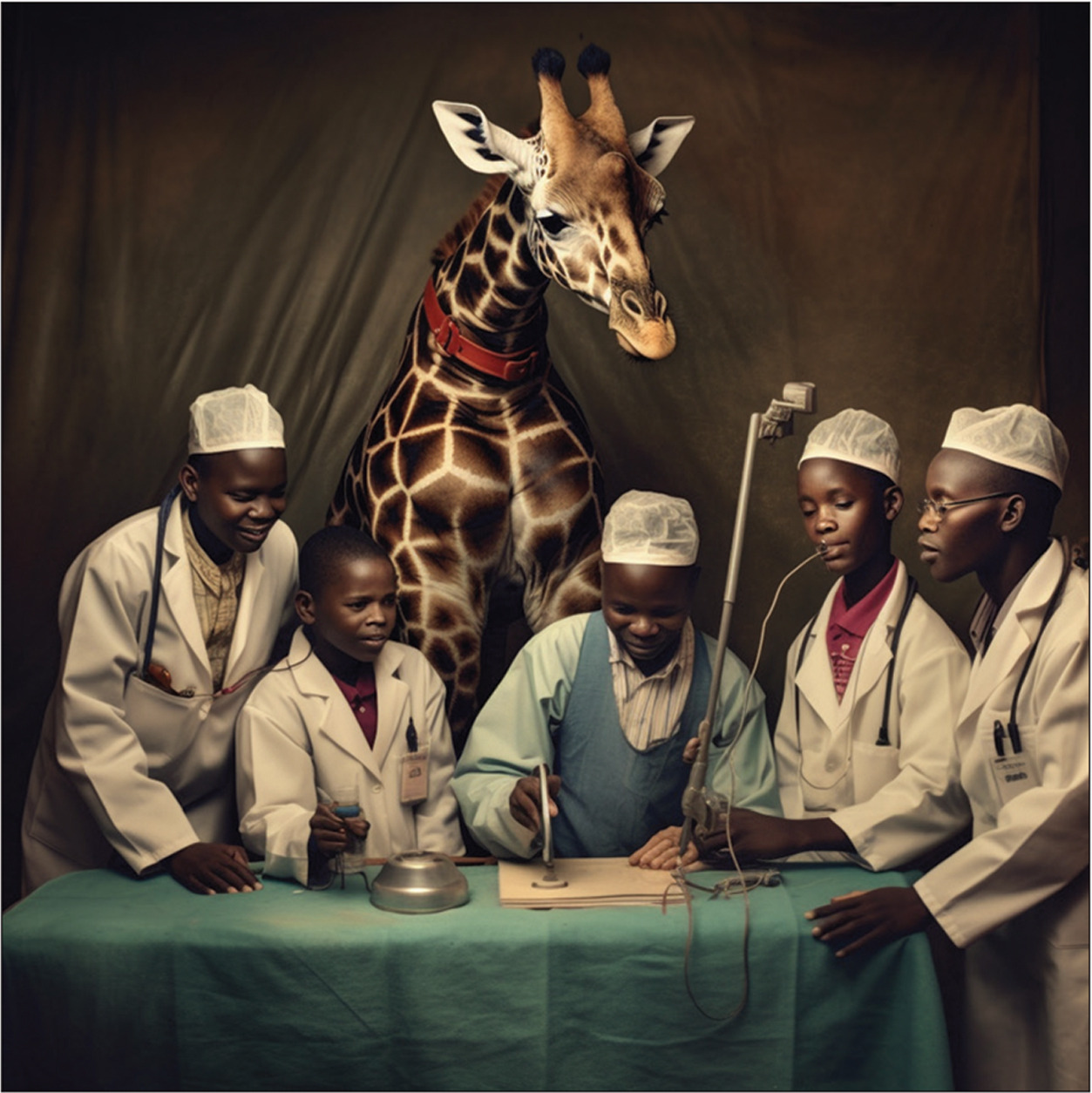

AI output in response to prompt "Doctors help children in Africa" (Alenichev, Kingori and Grietens, 2023)

Amidst the digital revolution and excitement over generative artificial intelligence programs like Chat GPT and Midjourney, ethical questions surrounding race, power, and representation loom large. On August 16, 2023, The Ethics Lab convened a dynamic panel discussion featuring Arsenii Alenichev (University of Oxford) and Nigerian visual artist Malik Afegbua (Slickcity Empire) to delve into these pressing issues from the diverse fields of global health and fashion, respectively. Acknowledging the co-constitutive relationship between power and technology, the discussion probed whether generative AI reproduces/challenges stereotypical representations of race and Africa.

Both speakers reflected on their experience with Midjourney, an AI program that generates images from text prompts. The conversation tapped into prevailing debates around algorithmic bias and the politics of representation. Malik reflected on his viral Elder Series, which uses AI to create fashion photos that challenge some of the ways in which elderly Africans are depicted. Similarly, Arsenii, together with Patricia Kingori and Koen Peeters, used generative AI to document racist assumptions that lie at the basis of much of the imagery in global health (read more here). Both speakers effectively argued that current configurations of generative AI encode biases and stereotypes and thus entrench rather than disrupt existing power configurations of power.

Arsenii painted a picture of generative AI as a window into the political nature of global health photography. Their project used AI as a barometer for the embeddedness of tropes and prejudices like the suffering (racialised) subject and white saviourism in global health imagery, which is often inscribed in social processes like coloniality, racism, and sexism. While their project initially set out to explore the capacity of AI to participate in political work that subverted and challenged these stereotypical representations, the team instead found in Midjourney an archive and reinforcement of these stereotypes. In effect, across numerous prompts, they found that the program coupled the reception of care with blackness and the provision of care with whiteness, while occasionally hallucinating exotic and racialised conceptions of Africaness.

Malik Afegbua’s contribution dovetailed much of the above, highlighting the twin problems of misrepresentation and underrepresentation. While the former captures how African culture, architecture, and heritage, for example, are portrayed, the latter observes that the training data used to develop generative AI programs like Midjourney is not sufficiently representative of the diversity of the world’s creators and artists. Malik described not just the limited ways in which elderly Africans were initially portrayed in the drawings he created with the AI, but also the work that is required to shift those images. He noted that his fashion show for the elderly, where he presented fashion-forward images of elderly Nigerians, required him to draw on a range of artistic skills, imagination, as well as knowledge of Nigerian fashion and ways of being.

These insightful reflections, anchored in ethics and weaving together the diverse worlds of global health and fashion were themselves generative, offering much food for thought regarding several themes and questions.

AI activism

First, the webinar clearly illustrated that AI can reinforce existing patterns of misrepresentation and misrecognition and that there are ways to disrupt these patterns. Malik’s art clearly demonstrated that such disruption requires commitment and mastery, not just in terms of developing better prompts to direct AI programs, but also, for instance, in leveraging other software and skills to train the AI to draw differently. Specifically, Malik noted that the work involved in developing his final images required him sometimes to export the AI’s drawings into Photoshop, for him to re-draw or fine-tune before re-uploading into the AI platform. To shift power, therefore, requires more than merely observing that the status quo is unsatisfactory: it requires both an ethical commitment to wanting to shift that status quo and the skill and tenacity to work with AI platforms to create the kinds of images that change the narrative.

Interestingly, his account of that experience is that his Southern location — based in Lagos, Nigeria — is not an absolute obstacle to critically engaging emerging technologies. Malik’s experience illustrated that costs are not a prohibitive barrier for Africans to do the work of disruption, which is a shift away from how Africa has typically featured in conversations around science and technology and opens up interesting possibilities for other Africans to do the same.

In the webinar, we discussed that AI Activism from the African continent would need to include a general call for more diverse training data, engineers and developers, and a commitment to improving these technological tools by listening and acting on feedback from black and African users. Equally, important questions need to be considered about who develops and defines African images (including images of Africans) and who benefits from those images. For instance, the images of poverty and dependence that Arsenii presented, powerfully serve to maintain the status quo in global health work. Shifting those images would serve African people keen to exert agency, but there could be pushback from people who gain from the existing power dynamics in global health. It would also need to reckon with important questions about language – most currently available platforms use English – and the for-profit orientation of the companies that currently own these platforms.

The peculiarity of essentialism

In observing the bias and stereotypes visible in AI’s visual repertoire, both speakers laid the charge of essentialism, which results in wrongs of misrepresentation and misrecognition. And yet, as intuitively agreeable as this claim is, there was something intriguing about this spectre of essentialism. Our thinking here borrows from a discussion on essentialism by Anne Phillips (2010).

There is tension between the critique that AI essentialises racial difference and the seeming communicative necessity of essentialism that underlies the prompting of AI. That is, there is a tension between the tendency to see essentialism as a bad thing and its inescapability as a constitutive feature of being human. We rely on (ideal) types and seem predisposed towards modes of abstraction that distinguish the essential from the contingent, yet critique AI for doing the same.

For example, Arsenii et al. are persuasive in outlining an essentialism that couples the provision and reception of care with white and black embodiment, respectively. There are different dimensions to the essentialism at play here – there is an attribution of specific characteristics to individuals that make up a group and there is even a possibility that these differences are attributed to the category itself, such that, for example, we move from generalising that “black and white people tend to be receivers and providers of care respectively” to the attribution of these roles/features to the racial category itself (“it is because they are black that…”). Taken together, both forms of essentialism inflate and naturalise perceived group differences, obscuring the socially and historically constructed nature of these roles.

At the same time, however, prompts like “African” or “black African” themselves seem to invoke a collectivity presumed to be a unified group. While they are rightly attentive to the ways in which AI reduces and (over)simplifies difference and complexity, isn’t it the case that at some level, our speakers were expecting the AI to churn out something recognisably African through their respective prompts?

This anticipatory essentialism, especially if the human psyche's tendency to pursue meaning, is worth exploring further if only to lay bare our own practices of essentialism and assumptions around authentic representation. For example, Arsenii and Malik criticised exoticised renditions of Africanity in terms of its associations with mud villages, wildlife, certain forms of clothing, etc. Is the problem not just the presence of essentialism but, more specifically, its content?

AI output in response to prompt "Doctors help children in Africa" (Alenichev, Kingori and Grietens, 2023)

Language and expectation

Finally, the webinar provoked some thought on discourse and how AI is often discussed and presented globally. Specifically, by using the term “artificial intelligence” and by emphasising that AI may be in competition with “the human”, the expectation is created that AI tools are more than simply technology – that somehow, they are intelligent and maybe even intentional in how they (re)produce the world. There is a parallel here with the field of genomics, where descriptions of DNA as being the “blueprint” of life or representing the “book of life” are often referred to as the reason for genetic exceptionalism in ethics discussions. The webinar prompted a crucial question: does the tendency to portray AI as nearly human in nature obscure crucial ethical issues that demand profound consideration, yet remain overlooked? Naomi Klein addressed this issue powerfully in her article for The Guardian titled "AI machines aren’t ‘hallucinating’. But their makers are," hinting at the depth of the problem. Likewise, Emily Bender, in a blog post, highlighted numerous profound ethical concerns regarding AI that are sidelined when attention is solely fixated on the purported existential threat it poses to humanity.

In conclusion, the webinar served as a catalyst for meaningful reflection on the evolving relationship between generative AI and representations of race, Africa, and Africans. It highlighted the dual nature of AI's impact – as a tool for potential transformation and a reflection of existing power dynamics. Ultimately, it emphasised the imperative for ethical stewardship and collaborative efforts in influencing AI's role in reshaping digital narratives.