Zeekoevlei Primary School provides basic education to children living in Lotus River, Phumlani, Pelican Park, Lekkerwater, Gymsebos, Reemvasmaak and surrounds. These communities are known for high unemployment, chronic poverty, gangsterism, low education levels and substance abuse. These communities were born out of the Apartheid government’s Group Areas Act of 1950 which aimed to geographically segregate the land and resources according to the various identified races. This resulted in non-white communities being located on the outskirts of the city, thereby away from resources and opportunities that enabled community development. This created systemic unequal access to resources and opportunities to thrive. Consequently, the lack of resources and socio-political issues has resulted in limited opportunities for health promoting occupations for children to engage in, which is critical for child development and health.

Don’t judge a book by its cover

Zeekoevlei Primary School has 875 learners enrolled. The average class size is 35-44. The school is a no-fee school, meaning that is gets subsidy from the Department of Education and parents are not required to pay fees. The school hosts many extra mural activities for the learners and is well resourced as a result of recent renovations funded by the government. It boasts a large hall, courtyard, sports field, gymnasium equipment, feeding scheme, administrative office, computer lab and jungle gyms. The Dept of Education successfully attempted to address the poor resources and infrastructures of the past. After conducting a context related assessment however, many intangible aspects were uncovered.

Many of the children at the school come from families who depend on child support grants to maintain their livelihoods. The high prevalence of criminal activity such as gang involvement, drug dealing, robberies and violent activities within the community are witnessed by children on a daily basis. Children are exposed to one narrative and internalize these social injustices and behaviour as normal. Many of the children idolize gang members because of their material resources, social power and brotherhood that belonging to a gang offers.

There are complex social issues that occur within the different households that adversely affect some of the learners at the school. This includes absent parents, parents abusing substances, domestic violence, high prevalence of sexual abuse and poverty. Access to nearby places available for recreation is limited which leaves very little for the learners to participate in outside of school. Resources and opportunities outside Lotus River remain inaccessible, causing adults and children to find alternative and often high-risk ways of maintaining their livelihoods such as being involved in gang-related activities such as theft, disposing of weapons after a crime scene, being a ‘look-out’ for police and being used as drug mules. Children are often unsupervised and left to walk around in the community and often become involved in unhealthy activities including underage drinking, smoking, abusing substances with parents, begging at traffic lights or remaining behind closed doors all day for safety reasons. Education is not valued by some families and some of the parents do not offer support at home when it comes to homework and other academic tasks. The consequences of all these issues have negative effects on the learners at school.

"...see the school as being embedded in the community and not that the community is embedded in the school"

The effects of deeper psychosocial problems are evident in the difficult and disruptive behaviour that the learners display. They easily react to conflict and frustration with violence by constantly fighting with classmates and teachers, unable to complete school work tasks or focus in the classroom and have difficulty expressing their emotions and communicating with others about how they feel.

From the outside looking in, the school is a pillar of change in the community. It is one of the only schools on the Cape Flats who do not have police presence nor security due to the trusting relationship between gang leaders and the principal. No shootings nor any criminal activities have occurred near or on the school premises. The newly renovated building is an example of how the government is trying to redress the inequalities of the past; but the government and public often only see the school as being embedded in the community and not that the community is embedded in the school.

So where does the Story of Change begin?

It begins with recognizing that ill-health is not only characterized by disease or impairment. Our communities are ‘sick’. This means that our children will grow up to be adults who will maintain the status quo and go onto living and pursuing unhealthy occupations. There is no medication nor treatment protocol for the social and political issues that are making our communities unhealthy. As Occupational Therapists, we recognize that both health and social sciences is needed to support the health and development of communities and its people.

The story begins with a candid conversation with Mr Graham Ritchie, the principal of Zeekoevlei Primary School. He shared his challenges as a principal having to hold the tensions of balancing the requirements of the Department of Education’s policies and regulations and the social and systemic injustices that his learners and staff face on a daily basis. Despite the new building and facilities, he still has the same challenges just in a different package.

We developed a shared understanding of this different role of OT and how it contributed to the health and development of the learners. He identified a group of Grade 3 and 4 learners who he described as ‘having the potential to engage in high risk behaviour and whose learning and development was being affected by underlying contextual factors’ and went on to mention that these learners were known for truancy and violent behaviour in the classroom. He felt that “there was nothing wrong with them like the other kids who go to traditional OT” but that they were ‘products’ of the systemic social issues of the community. The words violent behaviour was literally all that stuck in our heads! But we were committed to suspending our judgements and assumptions and needed to get to know the kids and they needed to get to know us.

Where to start?

A context related assessment was conducted by 4th year OT students in their Community Development Practice block in February 2019. Over and above the other participatory methods of assessment, it included playing with the kids during break times, sitting in class and assembly, chatting while they waited for a meal, playing soccer or hand ball in the quad and joining in on PT lessons. The assessment findings confirmed and assisted us further in gaining a deep understanding of their how their context impacted on their occupational engagement profile. We realised that directly addressing the socio-political aspects of the context was complex and required a long term commitment and presence in the community and so the focus was shifted to the learners as the vulnerable group and how to improve their current participation and health. A summary of the findings was presented to the Grade 3 and 4 teachers and in partnership co-designed a campaign to address the identified challenges that was a barrier to their participation. The campaign plan focussed on the greatest needs that teachers identified namely, finding positive role models for the children. Role models who reflected an alternative narrative to what they were being exposed to on a daily basis. It was decided to start a campaign that focused on bringing local Heros from the community to mentor Grade 7 learners who in turn will provide mentorship to the Grade 3s and 4s. In this way, both sets of children will benefit from healthy mentorship to encourage participation in health promoting occupations. It was envisioned that the campaign will run over the course of 3 years.

Using occupational science to analyse the findings further, the campaign was designed around deconstructing the dominant ways of thinking and doing around the occupations in their context by 1) introducing them to alternative narratives that went against the discourse that they have not been exposed to and 2) encouraging participation in health promoting activities available in the context. Having the learners work with the local heroes will enable them to see the possibility and benefits of engaging in occupations that are not high risk and destructive to their development and that of the community.

Where to start?

Our first priority in this initial phase was to build a shared understanding and develop authentic relationships with both the learners and teachers. We needed to gain their trust and in order to do this, we had to be very mindful of our privilege, power and position that we embodied while engaging with everyone. We needed to consider mindfully what were those intersecting identities that would make it possible for us to authentically connect with the kids and teachers. Discussing current news, sharing memories of playing common games when we were children, favourite TV programmes to watch, etc. We knew this would take time and definitely would be not achieved in 7 weeks.

We needed to develop partnerships with teachers so that OT spaces could be negotiated and fit into the teachers’ schedule. We were mindful of never disrupting the academic programme for the learners and we also wanted to ensure that the teachers stood behind the vision of the campaign.

Our second priority was to gain a deep understanding of the patterns of engagement and doing of the learners both inside and outside the school. Gaining an understanding of the socio-political aspects of the context both inside and outside the school and how that affects the children’s ability to participate in occupations that are health promoting was essential. We wanted to give the learners an opportunity to build and deepen their own understanding around the challenges in the community and consider their own solutions for change. We needed to carefully design and implement OT spaces that fostered acceptance, mutual respect, consistency, wholesome values and of course PLAY!

Our third priority was to develop a database of local Heros to engage with the learners. At this stage in the campaign, we were not clear on how or what those engagements would look like but we knew that the kids needed to be exposed to an alternative and positive narrative out of their own community.

What did we get up to in OT spaces?

When we met the identified learners, we discovered that their behaviour was indeed violent, aggressive and not conducive to learning and healthy play. In response to this, we immediately had to consider how to put healthy boundaries and consequences in place to support and shape healthier behaviour. We relied on our skill to practice responsively while drawing on our knowledges of child development and human occupation.

Friendly and supportive atmosphere

We used every day occupations as a means and as an ends. The ‘means’ allowed learners to freely enjoy playing simple games that they enjoyed and were familiar with like 3 sticks, on-on and hand ball, etc. They also enjoyed games that we introduced like red rover, balloon tennis, blind man’s bluff, mazes and obstacle courses etc. We allowed free play and this always resulted in soccer! The boys loved soccer! They also enjoyed playing on the computers in the lab (which because of their behaviour were never allowed by teachers to do), arts and craft and board games. Providing the learners with an enabling and inviting space for play and facilitating play was critical in addressing the occupational deprivation identified in the context related assessment.

At this stage, we could not recruit Grade 7 learners as they were busy with assessments and so we decided to begin getting local heros to spend time with the learners. Both Heros were born and raised in Lotus River and in fact used to live in the block of flats behind the school. They subsequently have both moved out of the community and have successful careers and showed interest in giving back to kids from the area. They fitted our criteria in that the heros were from the area and offered an alternative narrative that disrupted their social and economic circumstances. It was not easy finding heros and to be honest, our only criteria at this stage was for heros NOT to be a current gang member!

The ‘ends’ was aimed to get learners to engage in critical reflective dialogue, using techniques that promote action learning and dialogue, to support and challenge their thinking about participation and to disrupt their current patterns of engagement. Occupational Choice theory supported this focus of the campaign in that we respectfully made them conscious about how their context differed to other communities and how the issues in their context influences what they choose to do on a daily basis.

"Maintaining relationships, being consistent and demonstrating trust was critical in order for these dialogue spaces to be meaningful"

In block 2 we started recruiting Grade 7s who would be interested in participating and who showed potential for leadership but building relationships with them was a challenge due to mid year exam period starting and teachers were understandably reluctant to let the kids out of class.

We needed to identify existing healthy occupations that kids could engage in inside and outside school as new ways of thinking and doing needed to go beyond OT spaces. We needed to continue shaping behaviour of kids as their behaviour was precluding them in engaging in occupations that were good for them.

We found another local hero who is in the British army and arranged a Skype call with the Grade 7s. He shared pictures and newspaper clippings of his participation in the local rugby club in the 90s and explained his life’s trajectory since. He was able to share and connect with the kids current lived experience and was even able to name mutually known gang members that were still around. This was mesmerizing for the kids and watching them engage with the hero was invaluable. We realised that we needed to work more closely with heros on not only what they share but how they connect with the kids. We also needed to inspire the Grade 7s to be heros for the Grade 3s and 4s.

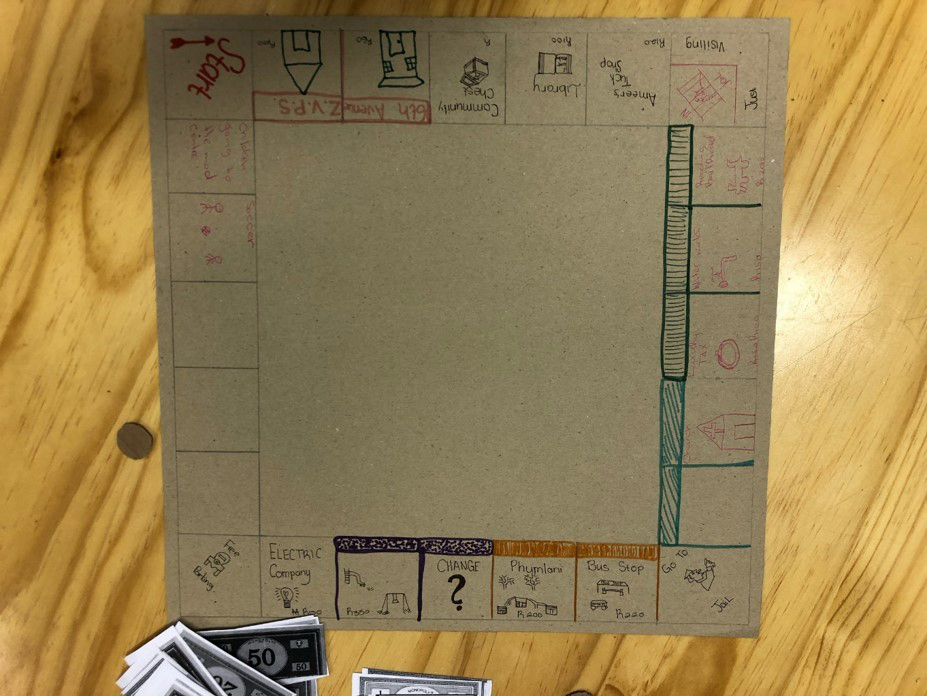

We noticed that Grade 3s and 4s responded well to board games and realised that the board games also helped us to bring containment to get the kids to sit down so that we could facilitate meaningful dialogue amongst them. The Grade 7s were also keen to play when we had sessions with them. The principal then alerted us to the extra mural programme that would be starting after the school holidays on Wednesdays after school. We saw this as the perfect opportunity to introduce and design healthy occupations for kids to engage in by a means of Board Games club, run and facilitated by Grade 7s. We saw this as space for participation but also mentoring if we built the capacity of the Grade 7s in the designing of the space. Unfortunately, as suspected, many children at the school were not attending extra murals. This made us turn back to occupational science theory again to try and understand why children are not taking up opportunities presented to them to participate in health promoting occupations?

Block 3 happened after a long break of 4 months and OT spaces had to be re-negotiate with teachers. We decided to bring in more indigenous games and activities for kids to engage in OT as a means to explore the ‘ends’ with kids as to why they don’t make use of existing opportunities for engagement in the community. At this stage we needed to re-establish relationships with the Grade 7s who were now preparing for their final exams. They decided to step out of the campaign and we respected that. We would then need to start the process of recruiting the out going grade 6s so that we would have Grade 7s for the next year. We gained critical insights as to how habitus and doxa played a large role in influencing learners motivation to initiate engagement. These issues were complex and we and learners needed more time to explore them further together.

Towards the end of block we focussed on securing a slot in the afterschool extra mural programme as a continued space for engagement for the kids (both Grade 7s and Grade 3/4s) in 2020 and identified a staff member who was willing to journey with us to ensure continuity in our absence.

So did it work?

While monitoring and evaluating the process, we confirmed that the kids were definitely rough and violent and most of the OT sessions entailed us running after them, getting them down from shelves they climbed on in the library, escorting them back to class, time out corners, breaking up fights, etc. By the end of 7 weeks, the kids managed to stay in OT for at least 20 minutes of the session and we noticed that kids wanted to come to OT and in-turn wanted to behave. Their behaviour was still aggressive and by the end of block, some kids were expelled for theft and stabbing and so never returned to school. The teachers noted that kids wanted to go to OT more but no improvement in their behaviour. This was fine as reducing high risk behaviour was not the main aim of OT, it was an expected outcome as a result of addressing occupational deprivation. We were strict with boundaries and rules in OT, so the consistency helped the kids to realise that they are responsible for their own behaviour, there are consequences and they have a choice. Behaviour was still destructive but we found that the kids were hungry for affirmation and positive feedback. Towards the end of block, there were many hugs and high fives and thin foundations for relationship were being laid. There was less fighting that required intervention.

The kids enjoyed engaging in fun playful activities but this was often stopped and disrupted due to behaviour. It was clear that occupational deprivation was being addressed but engagement at this stage was limited to confined and contained spaces. We observed that social aspects of participation still needed to be focussed on in order for learners to benefit from engagement.

The two local Heros that were idenitified came to spend time with the kids but their behaviour was so destructive that the session had to be shortened. We realised that the kids needed constant feedback on their behaviour. The Heros didn’t know what hit them but they too agreed to remain committed to the process.

In block 2 the kids responded better to positive feedback rather than only negative feedback and applying consequences. They also responded well to being given responsibilities in the OT spaces like sticking up the rules poster and setting up games, packing away etc. We also noticed the kids were able to stay in OT and were not running away. We decided to emphasize good behaviour and do appreciations and public praise in the sessions. They were also able to sit in a circle for 15 minutes and listen and engage meaningfully. They were able to greet and were even encouraging each other to behave in sessions with us not having to say anything. We introduced comradery songs like: “what do we say?, well done!”. There was very little fighting at this stage and kids could line up and return to class with no incidents or prompting.

In terms of participation the kids loved playing on the computers in the skills lab and we used this as reward for healthy behaviour. They were able to engage, self monitor and manage their behaviour and was able to enjoy the activity from the beginning to the end. The kids were starting to engage differently and experience the engagement positively. We noticed that in the dialogue spaces in OT, the kids also started sharing more about their home life and challenges they face. Although this was still superficial, we were gaining ground with trust. The kids still loved soccer, board games but we still needed to support them in translating their participation towards opportunities for engagement in the community and outside OT spaces. Teachers were noticing changes in the behaviour and response to discipline in the classroom and started to communicate progress in OT with teachers. We wanted to let teachers know that we were part of their team and relationship with teachers improved and they were starting to buy into the vision of the campaign.

We developed a relationship with the community hall’s manager who showed us the resources available for community members. Table tennis, indoor volley ball nets, balls, board games, etc but he too reported that the kids don’t make use of it. This again sent us back to occupational science to support our investigations as to why the kids don’t make use of these resources.

We secured an extra mural slot on Wednesdays at 2.30. The principal was happy for us to establish a computer club and board games club as these were the activities that the kids have responded to the best and expressed interest (actually begged us) in participating. We wanted to respect their occupational right to choose occupations that bring meaning and encourage development.

At this stage, in the 4th term, there was no fighting at all! The kids line up to come to and leave OT with no prompting. Their behaviour is appropriate and they have mutual respect for each other. The teachers don’t believe us, so we are planning on taking footage to show them. Some teachers have reported that they have noticed better behaviour in the classroom and PT lessons, less truancy and substance abuse at school in certain kids. The kids have also developed a comradery amongst them in that they are encouraging each other during play in break times and were very welcoming when we got two new kids. They are now enjoying a healthy balance of desk top activities and outside free play but most importantly are able to engage in reflective dialogue around the issues in their context.

We discovered the main reasons why kids don’t engage in activities is because they ‘don’t have lus [don’t feel like it]’ which highlighted the peer-related narrative to not engage as “this is what we all do, we don’t participate- whats the point?!” and practical safety reasons due to gang violence. We realised that the dominant discourse and habitus of the community is very powerful in stopping kids from participating more than safety reasons. We realise that a lot of work needs to be done in disrupting this discourse through heros and using occupation as a means and an ends to achieve this. Simply telling the kids to participate and make use of opportunities for participation is not effective. The kids need to experience doing and through that gain motivation to want to participate more.

While reducing high risk behaviour was an anticipated outcome, we still need to concentrate on strengthening the use of meaningful and purposeful occupation to address occupational injustice.

What’s the next chapter?

We plan on developing the Hero leg of the campaign further through marketing strategies and deepening partnerships to provide the type of mentoring needed to the Grade 7s. Work with new Grade 7s must continue and possibly recruit new grade 3/4 kids. The extra mural clubs (board games/computer/chess) need to be established and we are hoping we can partner with various people and organisations to collaborate with, outside experts or volunteers. A serious challenge that we need to address is the lack of involvement of parents. We plan on asking our site partners to brainstorm ideas on how to initiate this best. We intend on marketing the campaign locally but also provincially so that we can attract partners/sponsors to fund and support the initiative. Building networks with community organisations (local madrasah’s / Christian youth groups/ dance/karate/ etc) needs to be strengthened so that we can point kids to opportunities for participation and strengthen their social capital.

This story continues and we hope that you will follow us in how it unfolds.